Dogs - dingoes to puppaccinos

Inner West Sydney is one of the doggiest places in the Australia.

Even our most famous resident, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, meets world leaders with First Dog Toto.

Hear about…

the original dog of the inner west, the dingo

dogs in the Frontier Wars of Sydney

the Kangaroo Dog

how Australia's policy of poisoning dogs started here

the world's first dog-friendly cafe

Leichhardt Dog Training Club

the three dogs of Newtown, and

who is Maggie of Maggie's Rescue?

Show Notes

Welcome

By Deborah Lennis, D’harawal woman, local Elder and cultural advisor at Inner West Council.

It’s ok, we’re dog people [2:30 mins]

Turns out, Australians are ‘dog people’. 69% of households in Australia own pets, with dogs being the most common (48%), followed by cats (33%).

In case you’re wondering, everyone involved in this podcast has a dog.

Host Bernie Hobbs has Stella, her hairy little cinnamon scroll and couch companion.

And Jane, the producer, and John, the sound engineer, have a scruffy little terrier called Shroomie. Because he likes to stay close, Shroomie’s in the script recording sessions, dog-checking the facts.

Podcast guests

First Dog Toto [1:52 mins]

The inner west’s most famous dog is Toto, cavoodle of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese.

The local dog park [3:30 mins]

The Australian dog park is the modern civic hub we never wanted or asked for.

Eliza Reilly, 24 March 2023 in The Sydney Morning Herald

Most communities are communities of shared interest. Schools. Workplaces. Churches. These are communities that define us, that cement us as being a particular type of person.

What the dog park offers is a wonderful stripping of identities. Your politics, career or background no longer matter. Even your name isn’t essential. In the dog park you are known only – sometimes shamefully – by your dog.

There are shortcomings to this model of community. I’m aware there are some (probably) very nice people at our park that I’m never going to get along with, simply because our dogs don’t like each other.

Mark Barklett, 6 June 2023 in The Guardian

Inner West Council has 44 off-leash dog areas in its 269 parks. According to the council, dog walking is the second-most popular recreation in the inner west, and the council is trialing and introducing more dog parks.

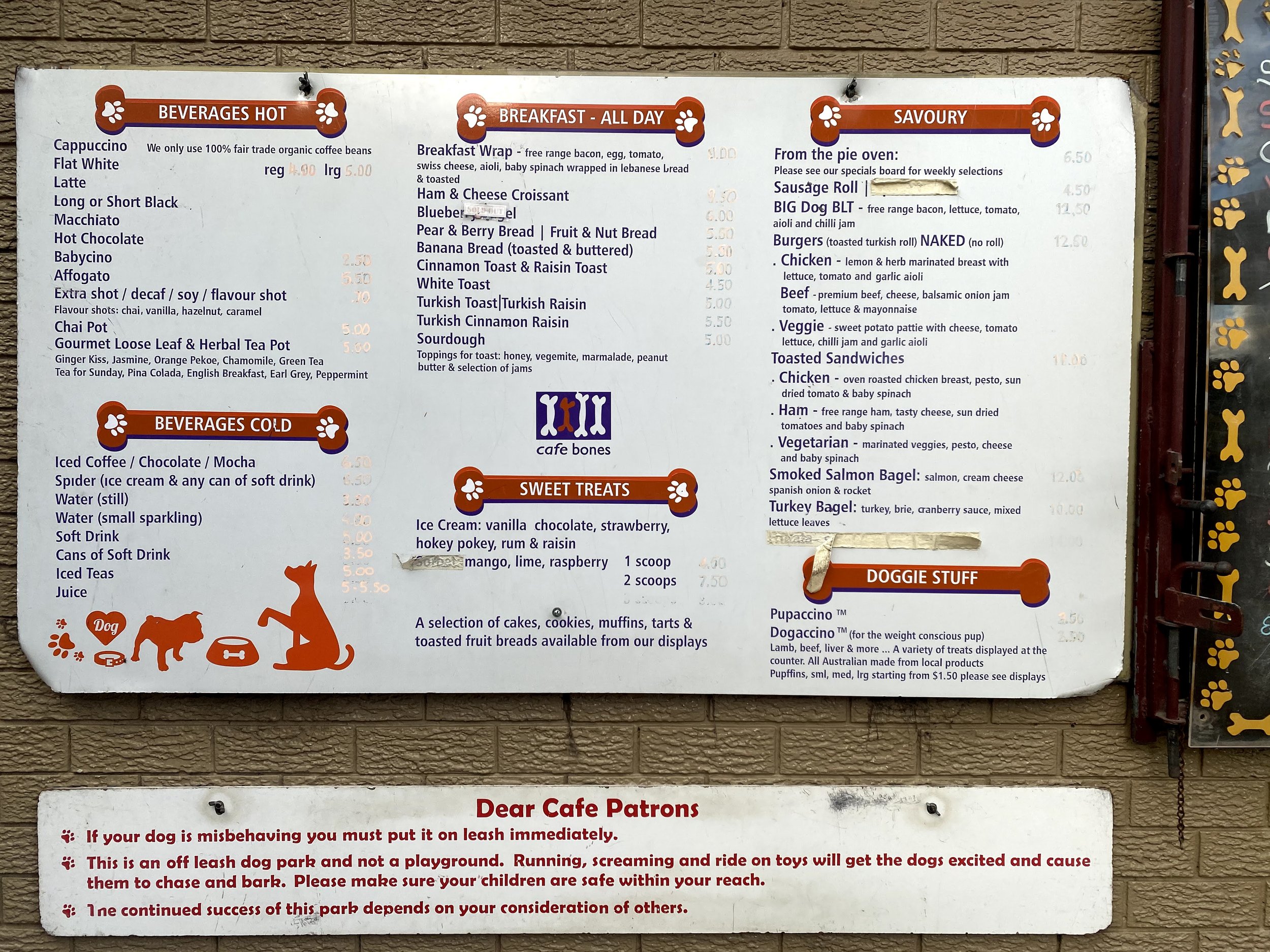

The world’s first dog-friendly cafe [6:00]

Established in 2000, Cafe Bones says it’s the world's first truly dog-friendly cafe.

The outdoor cafe is in Leichhardt, inside an off-leash dog park in the GreenWay.

As well as coffee and people food, they invented the world’s first doggy beverages the ‘pupuccino’ and the doguccino’, and the ‘pupffin’, a bacon and cheese muffin for dogs

Michael Lloyd-Jones, co-owner of Cafe Bones, says the pupuccino is “an homage to a cappuccino, but there's no coffee obviously, or chocolate or anything bad for dogs. It is a secret recipe, highly sought after, but unique to us.”

Leichhardt Dog Training Club [7:35]

Most Sunday mornings, volunteer dog trainers run classes at Hawthorne Canal Reserve, just near Cafe Bones.

Leichhardt Dog Training Club is a non-profit organisation that teaches people with puppies (from 16 weeks) and adult dogs. You pay a membership fee of $15 and then $2 a class - see the Leichhardt Dog Training Club website and Facebook.

Sydney was a dingo’s territory [8:50]

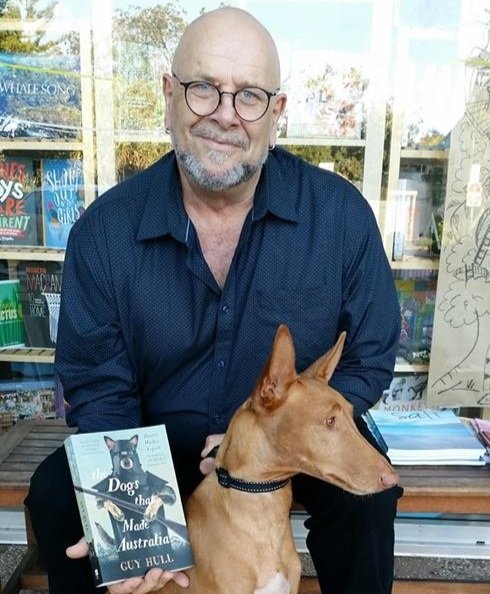

“Everywhere in Sydney, in the inner west, at some stage that was a dingo’s territory,” says Guy Hull, dog behaviourist, breed historian and author of The Dogs That Made Australia.

Fact check: Is a dingo even a dog? [8:55]

Yes, the dingo is Australia’s wild dog.

Like all dogs, dingoes are descended from the Grey Wolf, Canis lupus. Now it's scientific name is Canis lupus dingo.

The Australian Museum describes the dingo as ‘an ancient breed of domestic dog that was introduced to Australia, probably by Asian seafarers, about 4,000 years ago. Its origins have been traced back to early breeds of domestic dogs in south east Asia’.

Locations of dingo fossil remains in: Balme, J., O’Connor, S. & Fallon, S. New dates on dingo bones from Madura Cave provide oldest firm evidence for arrival of the species in Australia. Sci Rep 8, 9933 (2018).

Dingoes can (and did) live in most of mainland Australia [9:30]

Dingos came to live all over Australia from deserts to rainforests, woodland, mallee and grasslands. Nowadays dingoes are excluded from large areas of the southeast and southwest.

Dingo is a Dharug and Dharawal word [9:50]

The word ‘dingo’ comes from the Dharug language of the Sydney Basin, and Dharawal language of coastal Sydney. A tame dingo is a dingu and a wild dingo is a warrigal.

The Dharug and Dharawal people, and Aboriginal people all over lived with and tamed dingoes.

Many words for dingo

With more than 250 Indigenous languages including around 800 dialects, there's many words for dingo.

In Meeanjin/Brisbane, dingo is mirri and ngurun

On K’gari/ Fraser Island, the Butchella word for a camp dingo is wat-dha and wild dingo is wongari

In northern NSW to the Logan River, Southeast Queensland, the Bundjalung word is nalgal or ngalgal

Dingos and Dreamtime stories

Dingoes are in the Dreamtime stories of different Aboriginal nations, such as the Gariwerd/Grampians, traditional lands of the Djab Wurrung and the Jardwadjali people.

Dingo essential around the camp and for hunting [10:30]

The Aboriginal people of Sydney lived with dingoes. The dingo was critical as a hunting dog and as a source of warmth around the campfire, says Stephen Gapps, historian and author of The Sydney Wars: Conflict in the early colony, 1788-1817.

“They understood the dingo’s role. We are talking about the ultimate ecologists here,” adds Guy Hull.

20 years ago, dingoes were still living in the Sydney Basin, near Katoomba in the Blue Mountains.

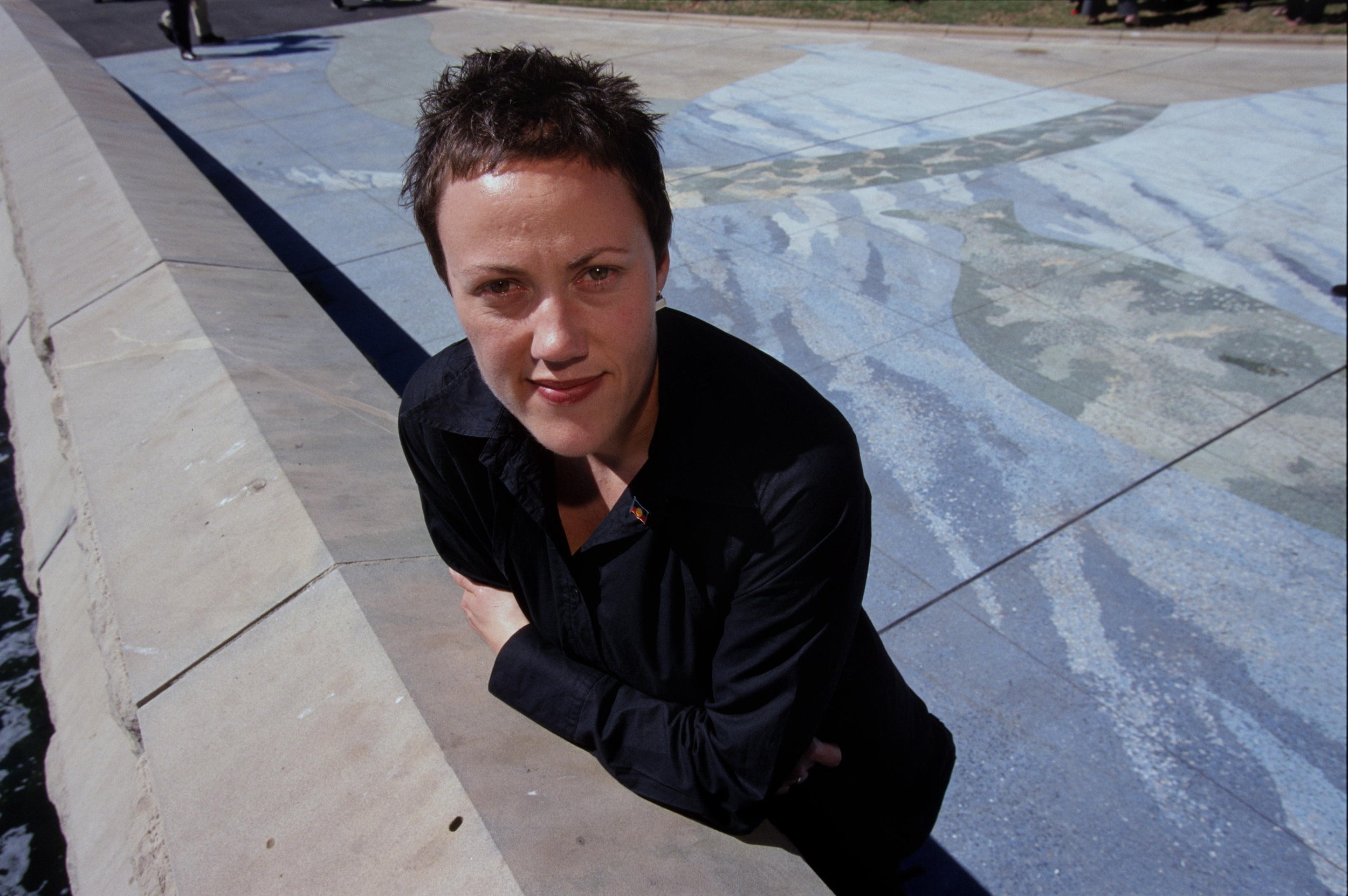

Dingoes and ceremony at Wuganmagulya (Farm Cove), Sydney Harbour

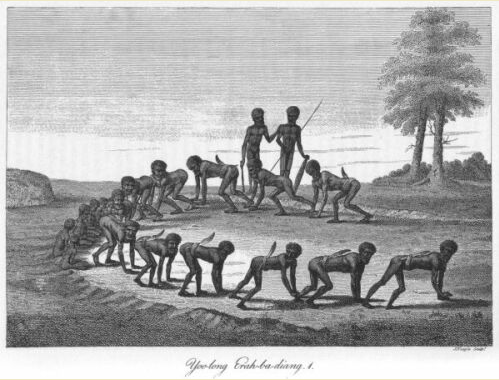

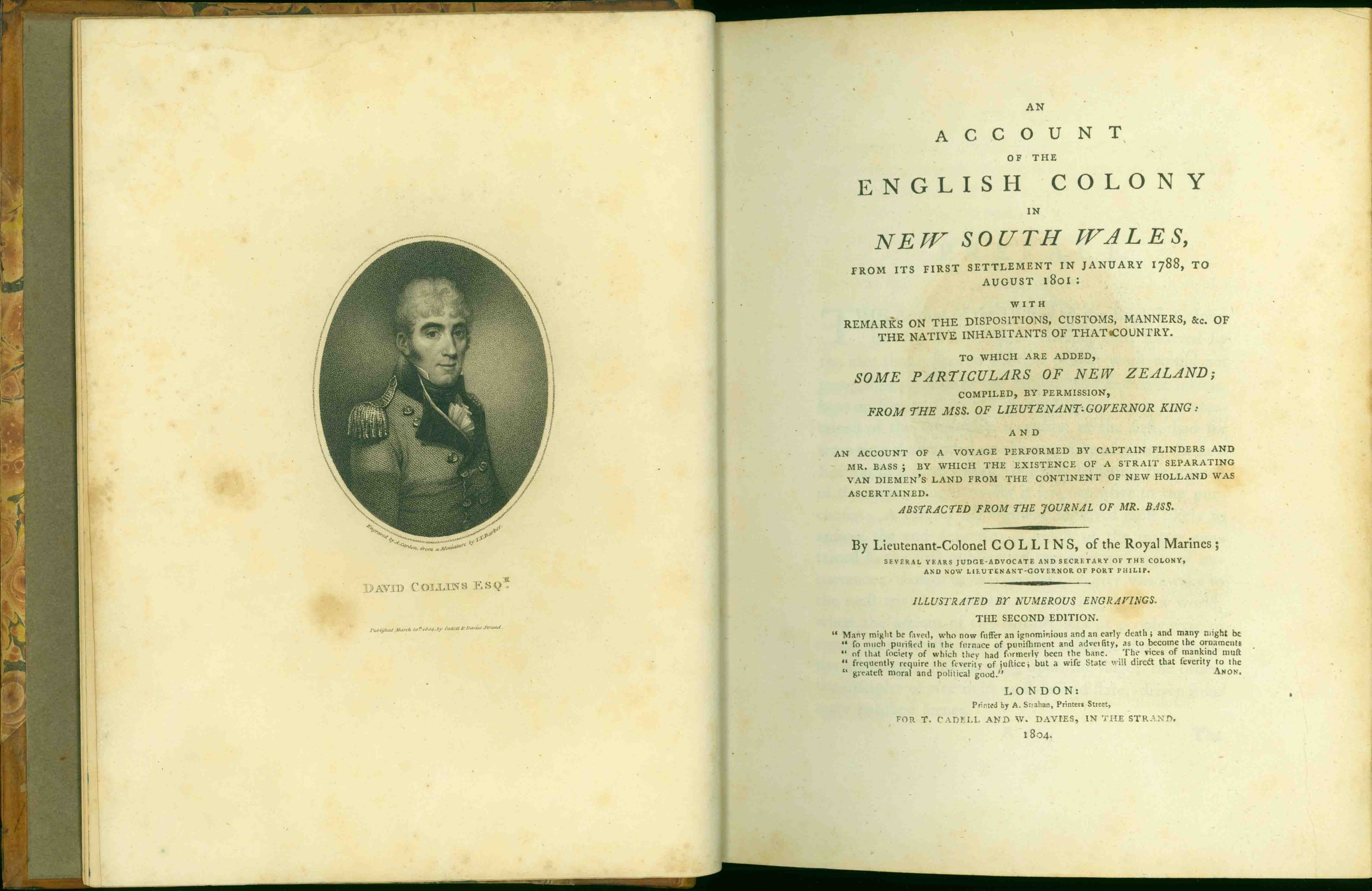

British colonist David Collins describes a ceremony of the Cammeray people, and he interprets the ceremony as being connected to dingoes.

On January 25, 1795 he describes the illustration and ceremony, titled Yoo-long Erah-ba-diang. It took place at Wuganmagulya (Farm Cove) on the southern shore of Sydney Harbour.

This land was an initiation ground for the Sydney Aboriginal people, and David Collins writes that its name in language is Yoo-lahng.

[The illustration] Represents the young men, fifteen in number, seated at the head of the Yoo-lahng, while those who were to be the operators paraded several times round it, running upon their hands and feet, and imitating the dogs of the country.

Their dress was adapted to this purpose; the wooden sword, stuck in the hinder part of the girdle which they wore round the waist, did not, when they were crawling on all fours, look much unlike the tail of a dog curled over his back.

Every time they passed the place where the boys were seated, they threw up the sand and dust on them with their hands and their feet.

Wuganmagulya is now part of the Sydney Botanic Gardens. In 2000, Gurindji woman and artist Brenda L Croft designed a public mosaic artwork in memory of the original clans and those who did ceremony at the site. It depicts rock carving figures in terrazzo and stained concrete. The artwork is part of Sydney Sculpture Walk.

Invading a dingo’s territory [10:45]

“When the First Fleet came in 1788, the colonists plonked themselves not only in the territory of the people who were living there at the time, but plonked themselves in the middle of a dingo's territory as well,” says Guy Hull.

“The British are immediately offside with the dingo’’ [11:00]

Guy Hull explains that the British were never likely to be fan. After all, they’d just wiped out the last wolf in Scotland, after a century’s long pogrom to just get rid of any predator.

“By 1700, they had also long been extirpated from England and from Wales – though their old territory is commemorated in the form of names: Ulthwaite, Wolfenden, Wolfheles, Wolvenfield. Their deaths, too: Woolpit, Wolfpit, Woolfall,” the Guardian reports.

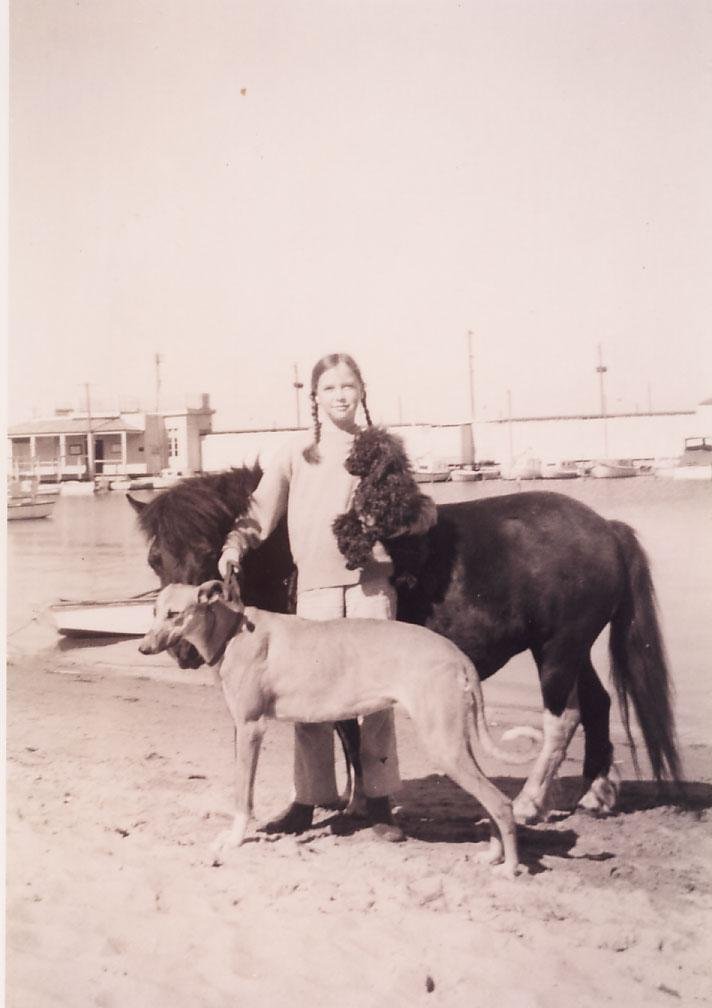

Dogs of the First Fleet

“This statue represents Governor Arthur Phillip's greyhound dog, Chara, one of several that he brought with him on the First Fleet - located within Pioneer Park, First Fleeters Memorial, at Eastern Suburbs Cemetery, Matraville, NSW.” Photo by Fellowship of First Fleeters on Facebook

From First Fleet journals we know that dogs survived the voyage and arrived in the Sydney Cove camp in 1788. There was a Newfoundland dog, Governor Phillip’s greyhounds, and assorted dogs and puppies that were probably terriers and spaniels. Other than that, there were no breeds specified.

Dingoes and the Frontier Wars [11:20]

The first British settlement at Warrane (Sydney Cove) had about 850 convicts and 550 crew, led by Governor Arthur Phillip. They arrived at Botany Bay in the "First Fleet" of 9 transport ships accompanied by 2 small warships, in January, 1788.

“The appropriation of Warrane by the First Fleet was the first step in an unfolding saga of devastation and dispossession of Aboriginal society.” (Museum of History NSW)

When the Aboriginal people of Sydney realised that the British ‘settlers’ were actually ‘armed invaders’, they used dingoes against them, in conflicts we call the Frontier Wars or The Australian Wars.

Early colonists such as David Collins report convicts being set upon by dingoes, says Stephen Gapps. “These convicts were going outside of the British settlement camp at Port Jackson on boats, to collect rushes as roofing material.”

‘Rushes’ are native grasses and reeds like lomandra and ‘Settler’s Flax’ that grow along Sydney Harbour. They have important traditional uses as food, medicine, fishing nets and basket weaving.

Dogs were a ‘critical resource’ in the Frontier Wars [12:00]

“Aboriginal people were actively setting the dogs on the convicts at this period of conflict. So the use of the dog as part of the arsenal of weapons by Aboriginal people, was one thing.

“But also, the Europeans found that they could set their dogs on Aboriginal people. And that happened later in the Frontier as well.“

Both sides in the conflict in Sydney, Aboriginal people and Europeans, in the 1790s in particular, found dogs to be a critical resource in conflict.

“A horse, a gun, and a dog”

Historian Stephen Gapps says the role of dogs in conflict in the early colony, is a legacy that continued when the British invaded and settled Aboriginal land beyond Sydney.

“So if you had a gun, a horse, and a dog, you had the three ingredients of protection in the bush.

Those three ingredients were critical for colonists, for stock workers going out in the bush, not just for hunting, but for protection and for warning. So the dog's role has often been understated. And the same with the horse.”

First ‘Australian’ poem includes a hunting dog

The first poem published in Australia on an Australian topic appeared in the Sydney Gazette on 16 June 1805.

Called Colonial Hunt, it describes a settler, his dog and his gun going into bush around Sydney to shoot a “wallaba”, as described by Ken Gelder and Rachael Weaver in their book The Colonial Kangaroo Hunt.

With my dog and my gun to the forest I fly

Wherein stately confusion rich gums sweep the sky.

Ken Gelder and Rachael Weaver point out that “even at such an early stage of settlement, [Colonial Hunt] already imagines a space through which a settler can travel, and hunt, freely and without interruption… There is no sense in the poem of early colonial Sydney and its environs as a site of military occupation and frontier violence.”

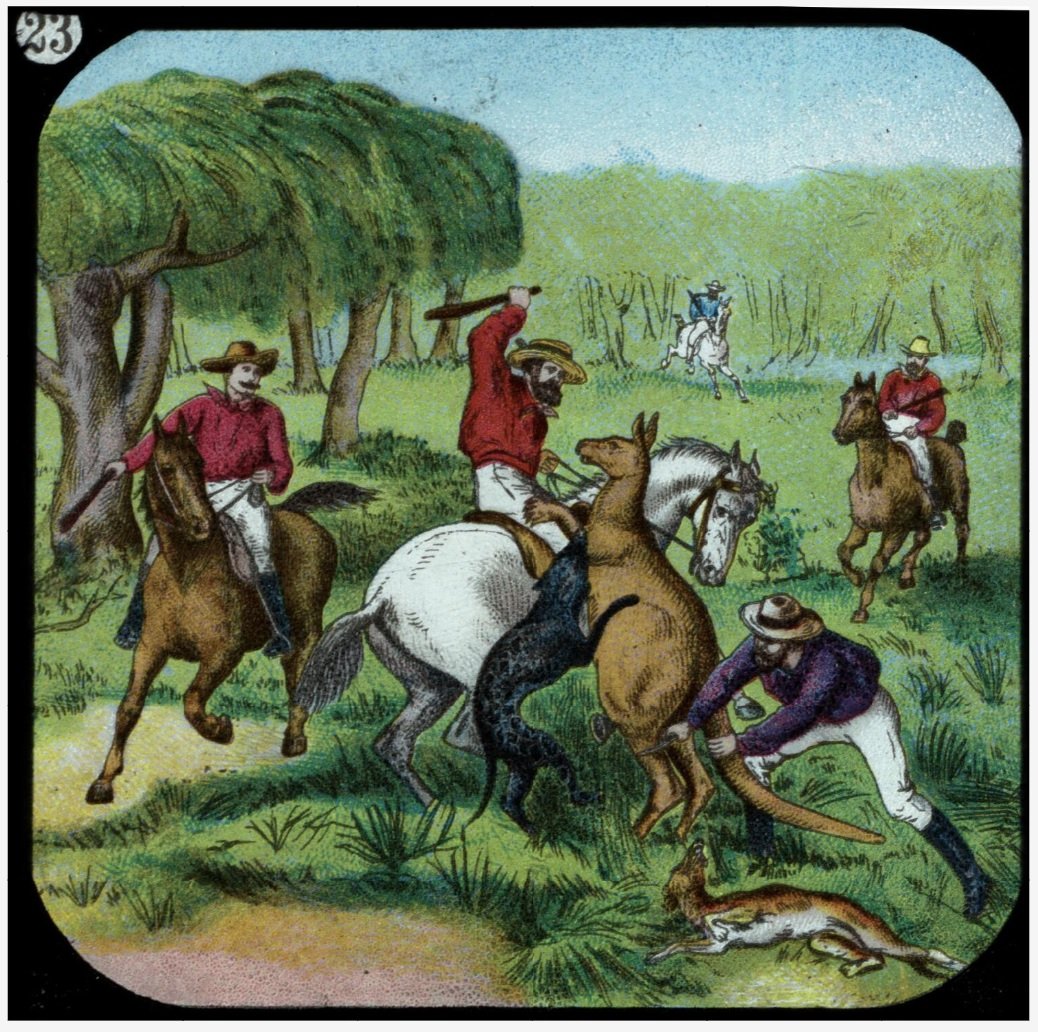

Hunting kangaroos with dogs [12:40]

The Colonial Kangaroo Hunt by Ken Gelder and Rachael Weaver and Black Emu by Bruce Pascoe describe how Aboriginal people all over Australia have been hunting kangaroos for food for thousands of years, using different methods like fire, nets and pursuit with dingoes.

Eastern Grey kangaroo of Sydney [13:10]

The kangaroo endemic to the Sydney region is the eastern grey kangaroo, or the ‘grey scrubber’ as they call them, says author Guy Hull. “It's a creature of the woodland and clearings and open spaces.”

Stephen Gapps says that if you've ever been out in the bush where kangaroos are not tame and not used to seeing people, you see that from a kilometre away, the kangaroos will flee.

“Because historically they're used to being prey and hunted. They were traditionally the prey of Aboriginal people. They were wary of humans.”

In the early colony, protein was in pretty short supply. The British could keep taking local fish and oysters, which they did, and they could eat the precious cattle and sheep they brought.

Or they could eat the protein that was jumping all around them.

1788 Watkin Tench eats dingo’s leftovers

“But taste is overruled by sheer necessity. The kangaroo’s carcass is so sought after in the hungry colony that at one point Tench and some others are driven to feast on carrion: ‘I once found in the woods the greatest part of a kangaroo just killed by [wild] dogs, which afforded to three of us a most welcome repast.’ “

pg 238 Tim Flannery (ed.), Watkin Tench’s 1788 , Text Publishing, 2009, in Gelder, Ken, and Rachael Weaver, The Colonial Kangaroo Hunt.

The inner west suburb of Petersham was called ‘Kangaroo Ground’ [13:00]

“One of the interesting things about here in the inner west is that Petersham was the nearest open space to this early colony, where there were known to be lots of kangaroos. It was still bush, but it was more open than around the [Sydney] Cove, ” says Stephen Gapps.

Kangaroo Ground also included the current suburbs of St Peters, and Newtown, including Sydney Park. The Gadigal and Wangal people hunted kangaroo on the grasslands there, and fished and camped at the swamps, creeks and rivers that crisscrossed the area.

1790 A newfoundland tries to hunt a kangaroo

“… It has been reported by some convicts who were out one day, accompanied by a large Newfoundland dog, that the latter seized a very large kangaroo but could not preserve its hold. They observed that the animal effected its escape by the defensive use it made of its tail, with which it struck its assailant in a most tremendous manner. The blows were applied with such force and efficacy, that the dog was bruised, in many places, till the blood flowed.”

John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales , J Debrett, 1790, pg 180-81 in Gelder, Ken, and Rachael Weaver, The Colonial Kangaroo Hunt.

Two ways to hunt kangaroos - guns or dogs

Watkin Tench was a young lieutenant in the Marine Corps and arrived with the First Fleet. In his 1793 book A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, he describes two ‘standard’ methods of killing kangaroos, “either we shot them, or hunted them with greyhounds”.

Muskets no good [13:45]

“It was really hard, surprisingly it might seem, for Europeans with a musket to be able to shoot kangaroos,” says Stephen Gapps.

The Europeans had Brown Bess muskets that were “just human killers at 50 yards. But as a hunting weapon, they was hopeless,” says Guy Hull.

Hunting kangaroos with greyhounds [14:00]

Since they can't shoot themselves a kangaroo for dinner, the British have another plan. Dogs.

They head off with their hunting dogs to Petersham, aka Kangaroo Ground.

“The governor would've let them use his greyhounds to start coursing them, and ‘coursing’, we mean chasing them. But greyhounds are very lightly built. They're built for really chasing smaller animals like hare and even smaller rabbits,” explains Guy Hull.

Skippy looks sweet but kangaroos kill a lot of dogs [14:20]

“Skippy looks like she's sweet and kind and harmless, but they kill a lot of dogs."

And kangaroos occasionally kill people.

Guy Hull says that kangaroos are the most dangerous terrestrial animal in Australia, and they're maybe the most dangerous herbivore in the world when they're cornered.

“They can grab a dog and disembowel them with their big toes. They get into water and then grab dogs and stand on them and drown them. So they've had thousands of years practice doing this with dingos.”

Dogs, kangaroos and sheep

“Kangaroo was the Sunday dinner for dingoes” [18:05]

The main prey of the dingo was kangaroo, says Guy Hull. And it’s the only predator of the kangaroo.

“Normally dingoes are solitary hunters, but they'd have to work as a pack or more, or at least more than one or two to, to catch a kangaroo. Pretty hard work doing that. And kangaroos are very lean and have no fat.” Watch BBC video of dingoes in a pack hunting kangaroos.

Sheep on the menu for dingoes

The colonists brought sheep that were “slow, easy to catch, easy to kill, and fatty, and really delicious”, says Guy Hull. “As soon as the dingoes found those, they went, ‘Oh, I don't think we'll waste our time getting ripped apart by the local kangaroo. We're just gonna eat these things.’”

Governor’s sheep attacked

The first attack by dogs on the colony’s livestock happened to the governor's sheep.

Author Guy Hull think that because it happened in daylight, it was probably a domestic dog. But dingoes were seen as the culprit because “dingoes got the blame for everything.”

Sheep in folds at night [16:20]

People would ‘fold’ their sheep at night - put them in a pen. Guy Hull says the dingo and the wild dog problem was so bad in the early Sydney colony that the dogs were climbing the fences and launching themselves on the stock in those folds and killing stock them.

1804 attack at Long Cove

In 1804, the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser reported:

On Tuesday night last a dreadful ravage was made at Long Cove by native dogs. Six ewes were found dead, 11 others were torn and mangled so shockingly as few were expected to recover from their wounds.

Dog laws begin

It didn't take long for the dog population to grow in the British settlement at Sydney Cove, to the point where a ‘public order’ was deemed necessary.

One early account of control over dogs in the British camp is recorded in November 1797: An Account of the English Colony of NSW Vol 2 by David Collins.

Dogs had increased to such an extent as to occasion their becoming the object of a public order, restricting the number kept by each person to no more than were absolutely necessary for the protection of his house and premises.

Much mischief had been done by them among the hogs, sheep, goats, and fowls of individuals.

1807 Governor Bligh’s public order [17:05]

In 1807 NSW Governor Bligh made a proclamation that, because of the number of sheep and lambs being killed in and around Sydney, that all dogs were to be immediately destroyed - except those owned by officers and respectable housekeepers, kangaroo dogs, and house dogs.

1811 Plan for the destruction of native dogs [19:10]

The Reverend Samuel Marsden, the “Flogging Parson”, and Gregory Blaxland and some other sheep growers put a bounty on dingoes.

It was the rum colony back then, so they were offering rum for people to kill as many wild dogs as they could possibly find.

The sheep farmers did offer a non-alcoholic alternative - one pound sterling for the complete skin of a fully grown native dog, and 10 shillings or half a gallon of spirits for the complete skin of a native pup.

That was the first time a bounty system or systematic extermination was trialled in Australia, and it started in New South Wales, in Sydney, says Guy Hull.

1814 First dingo poisoning reported

The first instance of using poison to eradicate the dingo was recorded in the Sydney Gazette, says Dr Justine Philip in The Conversation. She writes,

A “gentleman farmer” with extensive stock in the Nepean District initiated the operation. By applying arsenic to the body of a dead ox on his property, he managed to eradicate all the wild dogs from his landholding. The technique gathered a quiet following, though there were concerns that in the wrong hands this venture could inadvertently backfire on the penal colony.

That's when the poisoning started with arsenic, and “how they were able to start wiping out the dogs, because dogs are scavengers. Poison up and meat throw it out,” says Guy Hull.

In 1818, a scientific discovery enabled mass production of a highly toxic, stable and cheap poison known as strychnine. Strychnine became an essential item in the Australian farmer’s toolkit, and became used widely to poison dingoes and feral dogs.

“You put sheep here, you declare war on nature. So that's the way that it went.”

1852 Use of strychnine mandatory

Strychinine became an essential item in the Australian farmer’s toolkit, and by 1852 its use on landholdings was mandatory to control unwanted wildlife. In 1871 author Anthony Trollope wrote in his observations of Australian life:

On many large runs, carts are continually being taken round with (strychnine) baits to be set on the paths of the dingo. In smaller establishments the squatter or his head-man goes about with strychnine in his pocket and lumps of meat tied up in a handkerchief.

Over the course of the 19th century, the Australian economy became irreversibly dependent on this industrial agrochemical farming system.

How Australia made poisoning animals normal by Dr Justine Philip

It's argued that this is how poisoning animals in Australia became normal - we got started on dingoes 200 years ago.

Kangaroo Dogs

Needed a more robust dog to hunt kangaroos [15:30]

The colonists soon found that they needed a more robust dog than the greyhound to hunt kangaroos.

Guy Hull says that with subsequent fleets, the colonists brought bigger, more robust running hounds, like Scottish deerhounds. These were bred with greyhounds to make a breed called the ‘kangaroo dog’, sometimes called an Australian staghound.

“They were fast, they were maneuverable. They had that killer instinct and they were large enough to tackle kangaroos.”

The kangaroo dog was considered an essential dog, and breeding them was big business. These hunting dogs were “trained for the purpose of killing and sold at high prices.”

‘The national dog of Australia’

During the 1800's, Mr Hugh E.C. Beaver wrote in the 'The Standard' Newspaper, London:

This dog is essentially Australian, in fact, may be called the national dog of Australia. In the early days, everything was hard to get in the bush - flour was at a premium, (gun) powder and shot (were) not to be lavishly expended, and sheep were not to be killed except in some dire emergency. Kangaroo were plentiful... good to eat, and a dog who was fast enough to kill them, saved mutton, flour, (gun) powder and shot. A good Kangaroo Dog, therefore, was often a perfect godsend to a struggling squatter.’

From The Kangaroo Dog (Now Extinct) on JaneDogs website, where you can read more about the kangaroo dog.

Hunt clubs with dogs

Hunting clubs were established in New South Wales in the 1820s and, in Victoria, in the late 1830s, writes Ken Gelder and Rachael Weaver, in The Colonial Kangaroo Hunt.

1835 Sydney hunting club hunted the dingo

The Sydney Subscription Hounds was formed in early 1835; an early account describes a chase after a dingo, with the hunters dressed ‘in pinks ’ and their dogs finally ‘put off the scent by a Colony of Wallabies’.

Dingoes were identified as a pest by pastoralists early on, which meant that hunt clubs could regard killing them as an honourable act in the service of the colony. It helped if hunters could reimagine dingoes in the fox’s image— something the Sydney Subscription Hounds went to great lengths to encourage.

Ken Gelder and Rachael Weaver in The Colonial Kangaroo Hunt

1874 Sydney Hunt Club hunt kangaroo in Ashfield

The Australian Town and Country Journal reported on the hunt of a kangaroo for sport, in the inner west suburb of Ashfield, on 4 July 1874.

In consequence of the heavy rain on Friday, Saturday's fixture was postponed, and the Ashfield kangaroo hunt came off on Wednesday afternoon. There was a good attendance of members as well as others, and several fair daughters of Australia graced the meet, which took place at 2 p.m., close to Mr. Clissold's residence.

Long before the appointed time you would see a red coat wending his way to the place of meet, and each of them was made welcome by Mr. Clissold.

"Come in, gentlemen and refresh yourselves, as I am quite sure you will require it before you catch the kangaroo, as I have been feeding him on corn, so that he would be fit to give you a good run."

The Master of Hounds wended his way with fourteen couple of hounds, bearing towards an open piece of country about a mile to the left of the Ashfield Railway Station.

A dog having coursed the kangaroo at this point, he was compelled to seek protection in the river from which he was taken by George Hill and Mr Clissold, and carried back to his home in safety;

The decline of the kangaroo dog [21:15]

As soon as firearms became self-loading and bullets were available and strychnine and poison, kangaroo dogs weren't needed.

Guy Hull says that by the time the kangaroo dog really sort of disappeared, it was only being used way out in the bush.

“It got an ugly reputation and was really unfounded because all of those Greyhound breeds are lovely dogs. They might be killers, but they're very people oriented and make lovely house dogs.

It should be considered Australia’s national dog.”

The kangaroo dog is not recognised as a breed by any major kennel club.

Wild dog debate [20:35]

Wild dogs are still baited on farmland and in Australian national parks today.

The debate over wild dogs rages. One side says that there are very few pure dingoes in Australia and that we need to control feral dogs.

And the other side asks, are we actually poisoning dingoes?

The Dog Fence

Australia has a dingo fence 5614 kms long, running from Queensland to South Australia. It was completed in the 1950s to keep dingoes out of sheep farms.

It’s the longest barrier fence in the world, with a third of Australia ringed by the fence.

New research reveals the fence is affecting the development of kangaroos. The research team has called for more research into the effects of the fence. Co-author Dr Vera Weisbecker says, ‘The fence is a unique Australian megastructure, and a huge predator-prey experiment.’

The removal of dingoes to protect sheep has reshaped the landscape, and profoundly altered the ecosystem. “A lot of ecologists have deep concerns about the environmental impact of the fence,” Deakin University ecologist Euan Ritchie says.

Purebred dingoes more common than researchers thought, genetic study finds [20:52]

New research suggests dingoes don't have much dog ancestry and are more purebred than researchers thought.

The research suggested genetic analysis of dingo populations showed that dingoes have less dog lineage and there are more purebred dingoes in the wild.

The study indicated that previous research had overestimated the number of dingo-dog mixes and the lethal methods used to control "wild dogs" in Australia were actually controlling pure dingoes.

The Guardian dogs of Newtown [23:00]

If you've walked down the main drag of Newtown, chances are you've walked right past or rather, under these life-sized public artworks. Three dogs are up high on a poster bollard - Standing Dog, Running Dog and Walking Dog. They're also known as the ‘Guardian Dogs’ and are the work of inner westie artist and sculptor, Richard Byrnes.

The sculptures were commissioned by the local council of Marrickville in 2000 to:

Be durable public art: They're cast aluminum and “clean themselves.”

Reflect Newtown’s diversity and love of dogs: “If you stand on a corner in Newtown, you'll see someone walk past with a diamonte collared poodle at one instance, and then you'll see a bulldog with a rope around its neck, led by somebody else,” says Richard Byrnes.

Tell local history through art: Each of the dogs sculptures are particularised to the history and the location.

Standing Dog

Standing dog is on King Street, opposite Newtown Station. It's the one you'll see in most selfies and on cards and t-shirts.

This dog sculpture has a wooden kitchen spoon as part of its intestines, referencing King Street’s trip of restaurants. It also has cogs and wheels, and some machinery parts that reference Newtown as a former hub of the stage coach, coming through from Sydney to Parramatta.

Walking Dog

Walking Dog is also in Newtown, down Enmore Road. It’s outside the old post office opposite the Warren View Hotel.

Running Dog

Running Dog is right next door to Newtown in the suburb of St. Peter's.

St Peters was an industrial centre, with textile factors and brickworks. Richard included a large toothed cog to stabilize the dog’s back legs and reflect the area’s industrial history. The bicycle parts reference cycling at nearby Sydney Park.

Community affection for the dogs [25:30]

Richard Byrnes says that every time he goes past the artworks, he’s glad, because he see people decorating or dressing the dogs, or meeting under them.

“One of them one day was wearing a superman cape. they often attract the odd pink hula hoop over the top.”

“I walked past about three or four months after they were first installed, and someone had very beautifully put on a full leather dog collar, with a beautifully studded metal finish to it.”

“I've always loved Marrickville, I've been living here for over 20 years. It's a connection with your community. To have a public artwork in the very suburb you live in is quite special.”

Read more about the Guardian Dogs on Linda Daniele’s blog.

Australian dog shelters ‘over capacity’ [27:30]

For a nation of dog lovers, Australians are abandoning our pets at alarming rates, according to the ABC in May 2023. Most RSPCA shelters are over capacity, with hundreds of animals on their surrender waitlists. Why? Living costs, vet care, the impacts of covid and a ‘throw-away’ attitude.

There's also the law where (except in grownup Victoria) landlords can discriminate against dog owners.

And when dogs are dumped, animal rescue groups step in.

Maggie’s Rescue in Marrickville

Lisa Brittain, Operations Manager with two foster pups Chef and Baker. Lisa’s in the Maggie’s Rescue office at Addison Road Community Centre.

Maggie's Rescue is a foster-based cooperative that rescues and rehome animals within the Sydney area. They focus on rehoming, de-sexing and community education.

It is not a shelter, and all animals in care through Maggie’s Rescue are in foster homes.

”The idea behind Maggie's is not just that we are just simply rescue and rehome animals, but we're trying to make a difference to the community in which we live in, which is the inner west,” says Lisa Brittain, the Operations Manager at Maggie’s Rescue.

Lisa is also an original board member of the co-operative since it was founded in 2011.

They help dissecting of street cats and help people out with food and flea products.

Maggie’s Foster To Adopt program is designed to create a nurturing temporary home for homeless and abandoned companion animals, until a permanent, forever home is found. They’ve rescued and rehomed over 1900 companion animals.

Who is Maggie? [28:00]

Lisa Wright is one of the co-founders of Maggie’s Rescue. She didn't know Maggie for very long - just a day.

Lisa Wright and her family had moved from inner West Sydney to Brisbane temporarily. Lisa was volunteering with an animal rescue group in Brisbane when she got a phone call.

The woman on the phone said, “I've been told you are the person to see about rescuing a border collie.”

That border collie was Maggie. She was nine years old and living under an old house, a Queenslander near Ipswich. The house was closed and was dark underneath.

In Lisa’s top five cases of animal neglect [28:45]

Lisa says that “eventually when we did get Maggie, it probably was up there in my top five cases of animal neglect.”

“Her nails were probably about three quarters of an inch long and her coat was matted to her skin.”

Maggie was taken into foster care, but the foster carer later called Lisa in tears and said, “This dog is pacing, she's in pain.”

Lisa says that border collies are a breed that “absolutely live to make you happy. And part of the reason why I personally don't own a Border Collie is because of that. They'll work through pain, they'll work through distress, they'll work through your disapproval and still be trying to keep you happy.”

Animal Welfare League up at Ipswich took Maggie in for a vet check. She had masses throughout her abdomen and she was at end stage cancer in their opinion, said Lisa. “We made the really awful and sad choice to euthanise her. “

Now Lisa can talk about Maggie without crying, but she couldn't for a long time.

“I've often found this story very hard to tell, but my promise to her was that I would actually honor her. And if I did get off my tush and start a rescue, it would be named after her and all the Maggies in the world.

That's how Maggie's Rescue started. It was about her.”

A life-changing accident

In 2011, Lisa Wright and her husband were leaving for the movies and were in massive car accident. Lisa fractured her back in two places, compressed her spinal cord and had a head injury. My husband broke his femur into seven pieces.

“We were really in a bad way, ” she says.

In the long period of rehab after the car accident, Lisa reflected on life.

“It put things into perspective.

I just knew that I didn't want to do things I didn't want to do anymore. That probably comes from a position of privilege, in many ways. I had that opportunity to make choices about what I was going to do next.

I realised I love doing advocacy work. I wanted to start an animal welfare group. And we already had the name!”

Why a co-operative? [30:45]

In the days and weeks after the accident, Lisa Wright reflected on her past experience in rescue groups.

“I'd had these feelings about working in rescue groups where there's usually one person at the top and they're the big personality and they make all the big decisions. Yet there's always these amazing people around with incredible skills.”

“I really wanted - and this probably comes back to my inner west ideology - a cooperative where everybody's skills will come together.”

Lisa contacted a Brisbane friend that she’d met through rehoming a kelpie.

Her name was Lisa Warren and together, both Lisas registered Maggie’s Rescue as a co-operative on 14th of August, 2011.

Since Lisa Wright knew she’d be moving back to inner west Sydney, the co-operative was registered in NSW.

2011 Running an animal rescue co-operative from your home [31:20]

For three years, Lisa ran the rescue rehoming dogs and cats out of her home in the suburb of St Peters.

“My husband Mark and I tallied up the volume of dogs alone that came through our house. It was 172.“ That’s a lot of dog!

As well as that charming terrace slash kennel in St Peter's, the other place you'd come across Maggie's Rescue was the Addison Road Community Centre, affectionately known as Addi Road.

At Addison Road Community Centre from the start [31:45]

Over the years, Maggie’s Rescue has had a big presence on the grounds of Addi Road Community Centre in Marrickville. The rescue timed its adoption days with the weekly markets and Lisa’s husband walked around the markets fundraising for Maggie’s Rescue.

2013 Maggie’s Rescue moves to Addi Road [32:00]

The cooperative moved out of Lisa Wright's home and into a permanent space at Addi Road Community Centre in 2013. The folowing year in 2014, Maggie’s moved into a bigger space, where it is today.

Hundreds of volunteers [32:20]

Maggie's rescue has come a long way, thanks to its hundreds and hundreds of volunteers.

Full-time Operations Manager Lisa Brittain is the only paid staff member and volunteers keep the rest of Maggie’s running.

Lisa says there’s around 80 foster care volunteers, volunteers on the marketing team, Fundraising Committee and our Animal Welfare and Education committee.

There’s also volunteers that help markets and stalls and events like the Muddy Paws Festival.

Volunteer with Maggie’s or sign up as a foster carer.

Lisa Brittain’s advice for getting a rescue dog

“Listen to the rescue or the foster carer because they're the ones that live with the dog and know it best. Want to help the dog and not just have a dog.

She says that patience is the key with a rescue dog. “Give them to decompress and adjust to their new home, and realise that they may not fit into your lifestyle straight away. Respect them as an individual and give them time.”

In memory of Maggie [32:30]

For co-founder Lisa Wright, the memory of Maggie the border collie will always stay with her.

“I didn't want her life to mean nothing.

I guarantee you, there are a thousand Maggies out there right now, that really, really need people to just notice them and recognise them as being worth doing something about it.

You don’t have to start a rescue, but the Maggies of the world need to be noticed.

They just do.”

Episode transcript

Inner West Icons: Dogs transcript PDF and Inner West Icons: Dogs transcript Word doc