Callan Park - the green asylum

A stone goanna at Broughton Hall, Callan Park. Photo: Lyn Latella from Friends of Callan Park

Callan Park is inner west Sydney’s biggest green space.

It’s where you’ll find Callan Park Hospital for the Insane - closed but still standing.

Find out..

Why this spot was chosen for mental health?

How ‘green therapy’ came and went?

About the crocodile of Callan Park

How the community fights to keep it going, and

How the quality of our parks impacts mental health

Show Notes

Welcome

By Deborah Lennis, D’harawal woman, local Elder, and cultural advisor at Inner West Council.

Aerial photo of Callan Park’s Kirkbride block. Photo by Jason Bircher from Friends of Callan Park.

What is Callan Park?

‘A horseshoe-shaped valley that runs down to Sydney Harbour’ is how President of Friends of Callan Park, Hall Greenland, describes Callan Park.

“You won't find the like of it anywhere in Australia, because it is a colonial estate that is still intact and available.”

Callan Park is a heritage-listed site bordered by Balmain Road and Manning Street, Rozelle and Glover Street, Lilyfield.

It’s on Gadigal and Wangal land and runs down to Iron Cove and Sydney Harbour.

Today, it’s known for its heritage buildings - including the former Callan Park Hospital for the Insane/Rozelle Hospital - and its incredible parkland and trees.

At 61 hectares or 125 acres, it’s the size of a small suburb!

Why is Callan Park unique?

There are more than 200 buildings from various eras on the site, with the oldest being Garry Owen House, built c 1840.

According to the Callan Park Master Plan 2011, its features are:

Its location on Iron Cove and Sydney Harbour.

It’s the third largest open space in inner Sydney behind Centennial and Moore Parklands (320 hectares) and the Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain (64 hectares).

The whole of the site being listed on the State Heritage Register.

The exceptional heritage landscape buildings of the former Rozelle Hospital located on the site.

The cultural heritage value of the site in relation to the history of mental health in Australia.

The waterfront public open spaces, landscaping and gardens.

Remnants of natural bushland and wildlife habitat – one of the few remaining in the inner west of Sydney.

Aboriginal middens at Callan Point.

One of the few remaining beaches in the inner west.

Ongoing use by State-significant tenants including the NSW headquarters of the NSW Ambulance Service, and several non-government organisations like Writing NSW.

“Callan Park is a wellness sanctuary, bridging the gap between acute care and home life for those with mental illness, and contributing to the mental, physical and social health of the entire community.”

Black Wattle, a defining tree for Country

Tour guide Drew Roberts explains how the Sydney golden wattle tree (Acacia Longifolia), which he calls Black Wattle, is one of the defining trees for Country.

Drew Roberts from Shared Knowledge took us on an Aboriginal heritage tour of Callan Park. He says Black Wattle would have been of vital use.

How to make soap from wattle

In the tour, Drew got everyone on the tour to pick some wattle leaves.

Then - we folded them into a ball, put our hands around the leaves and held it down really tight.

Next, we rubbed around and around, until it felt a bit tacky and sticky.

We added a little water and kept rubbing, and then… soap!!

“I grew up with this, like most people grew up with Clearasil,” Drew said.

“This will actually get rid of lines, wrinkles, rosacea, and eczema. It's got so many usages. Once you rinse, you'll notice how soft your hands are. Imagine that on your face.

This is the reason my eighty year old Aunties look as if they're forty.”

Sydney golden wattle (Acacia Longifolia). Photo source: Aussie Bush Knowledge on Facebook

Black Wattle, the Mother tree

When we did the tour in mid-March, the wattle was just getting ready to come back into flower.

Drew says the wattle tree tells him when:

whales are going to be here

it's possible to eat oysters

it's possible to eat pippies

the fish have come out of the Parramatta River and come into the ocean, so then they no longer tastes like mud.

Because the wattle tree ‘tells you what to do’, Drew says “We call the wattle the Mother Tree. It tells you what to eat, it cleans you and helps you, like your mother does.”

Many thanks to Drew Roberts of Shared Knowledge for kindly letting me record some of his tour. Shared Knowledge offer tailored tours, and specialise in business services, education, Aboriginal experiences and catering.

Callan Point: a place for families

Deborah Lennis, the Cultural Advisor for Inner West Council, says that before colonisation, Callan Point was a major site for families.

Gadigal and Wangal people of the Eora Nation have lived in the inner west for at least 20 00 years.

Women did a lot of the fishing, usually in bark canoes, the nawi. Deborah says the family would sit at the top of the point and there would be storytelling, songs, movement…

According to the NSW State Heritage Inventory, “Callan Point is considered to be the most important Aboriginal archaeological site remaining on the southern shores of Sydney Harbour. Callan Point also contains rare examples of pre-European vegetation and unique European rock carvings.”

Shell middens at Callan Point

The middens at Callan Point are estimated to be over four and a half thousand years old. A midden is a mound or deposit of remains, usually of food.

The Callan Point middens are coastal middens, made of the remains of shellfish such as mussells (dal-gal) and rock oyster (badangi) in the Dahrug language of the Sydney basin.

Dal-gal and badangi were caught and eaten in the same place, year after year.

Read more about the seafood caught and eaten by Aboriginal coastal people at the Australian Museum.

What is a midden?

Shell middens are deposits in which shells are the dominant visible cultural items. They are the location of campsites and the shells are principally the remains of past meals.

Some middens consist only of shells, but others contain a range of materials including stone, bone and shell artefacts, animal bones and pieces of ochre, as well as charcoal and hearths (fireplaces).

They vary widely in size from a few shells scattered over the surface of a small area to thousands of shells extending tens of square metres in area, and several metres in depth with complex stratigraphy which has built up over thousands of years.

Wangal people and First Contact

It was the makers of those Callan Park middens, the Wangal people, who encountered the British First Fleet on their land, on the 5th February 1788. Less than a year later, smallpox hits. The Aboriginal population is decimated by at least 50%, if not 80% potentially, according to historian Stephen Gapps.

The Wangal people that survived both worked with and resisted colonisation. The British camp at Sydney Cove expanded and became Sydney Town.

The colonists claimed the middens at Callan Park and middens all along Sydney Harbour foreshore. Why? Brick buildings need lime mortar. And shell was the main ingredient. Convicts worked in Shell Gangs, hauling and crushing shells, which were then burnt to make lime.

The middens were so dense that the Shell Gangs of over 30 men were still collecting shells from Callan Park foreshore at Iron Cove, 40 years after settlement.

Historian Roslyn Burge says ‘Aboriginal middens built Sydney.’

Early colonial history of Callan Park

Gadigal and Wangal land was taken and given to settlers as land grants. Callan Park was a series of gentlemen’s estates full of European trees, and orchards of lilies and oranges - naming the suburbs of Lilyfield and Orange Grove.

Mental Health Pioneer #1 Frederic Norton Manning

Doctor Frederic Norton Manning was asked to run Sydney’s lunatic asylum in 1867 - using the language of the time - at Gladesville. Manning took the job, on one condition: that he could do a research trip overseas.

Over eleven months, he visited 67 mental asylums, taking copious notes, across Europe and America.

On his return in 1868, Dr Manning wrote Report on Lunatic Asylums, now in the Public Domain. The video below is a presentation on that report.

Mental health reform in Europe and the US

When Manning was doing his ‘Contiki Tour’ of asylums, reform was well underway - both in Europe and the US. And he got to see new, more humane and progressive mental healthcare.

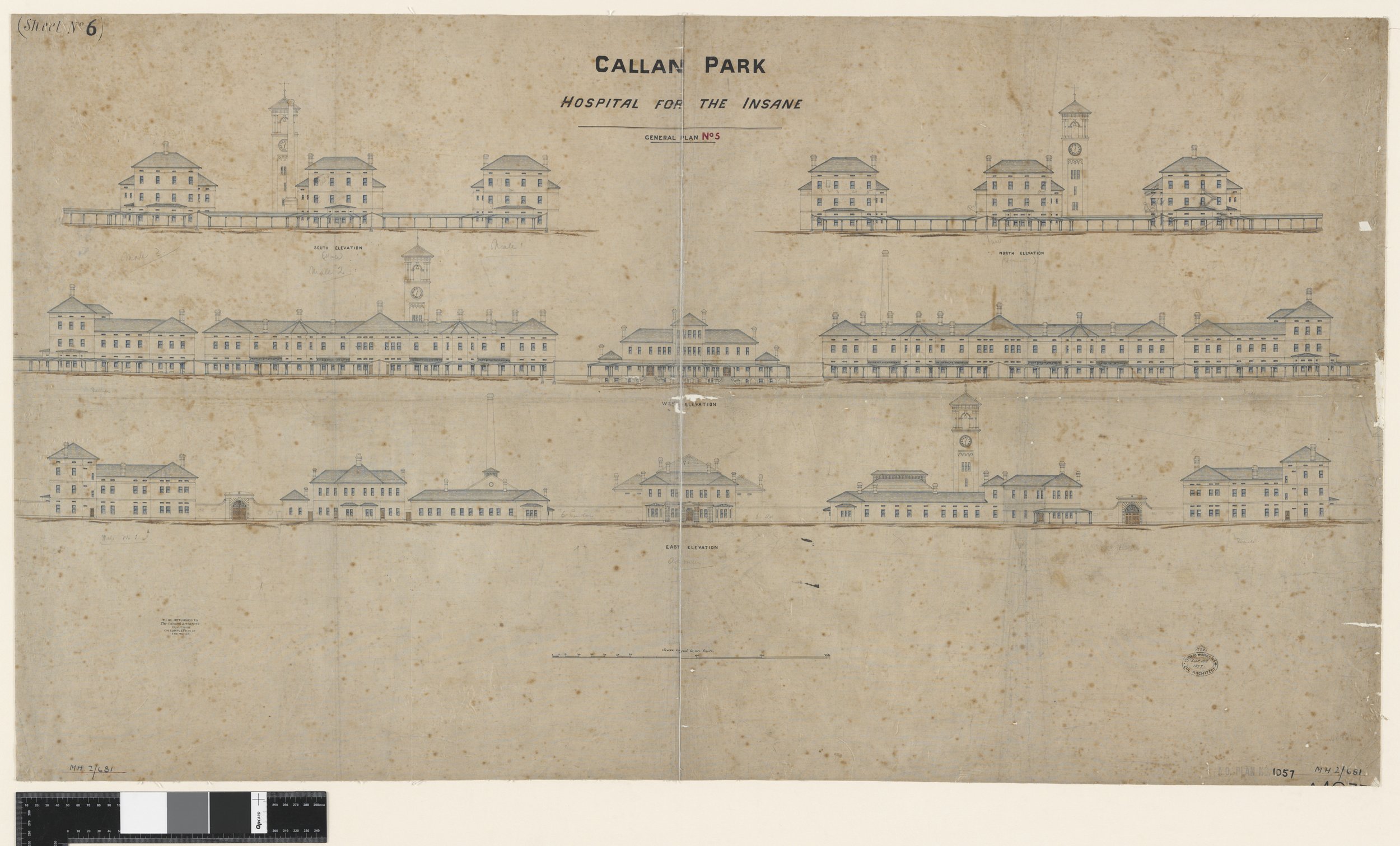

Frederic Manning was influenced by Thomas Kirkbride, an American psychiatric pioneer who proposed that asylums built in secluded, rural settings would be more therapeutic.

In his journal article Kirkbride’s Architectural Stigma of Mental Illness, Daniel Bristow writes that ‘Kirkbride did not intend for his hospitals to become warehouses for the untreatable. He thought these hospitals would help patients regain their health and self control through structured living and soothing surroundings. Armed with their rediscovered sanity, they would ideally return to the community as productive citizens after a brief hospitalization. But many patients did not recover and spent years in these grand buildings as chronic victims of a neglected system.’

1871 ‘Callan Park Estate’ for sale

By the early 1870s Tarbin Creek Asylum at Gladesville was incredibly overcrowded. The land that we now know as Callan Park came up for sale, as subdivided lots.

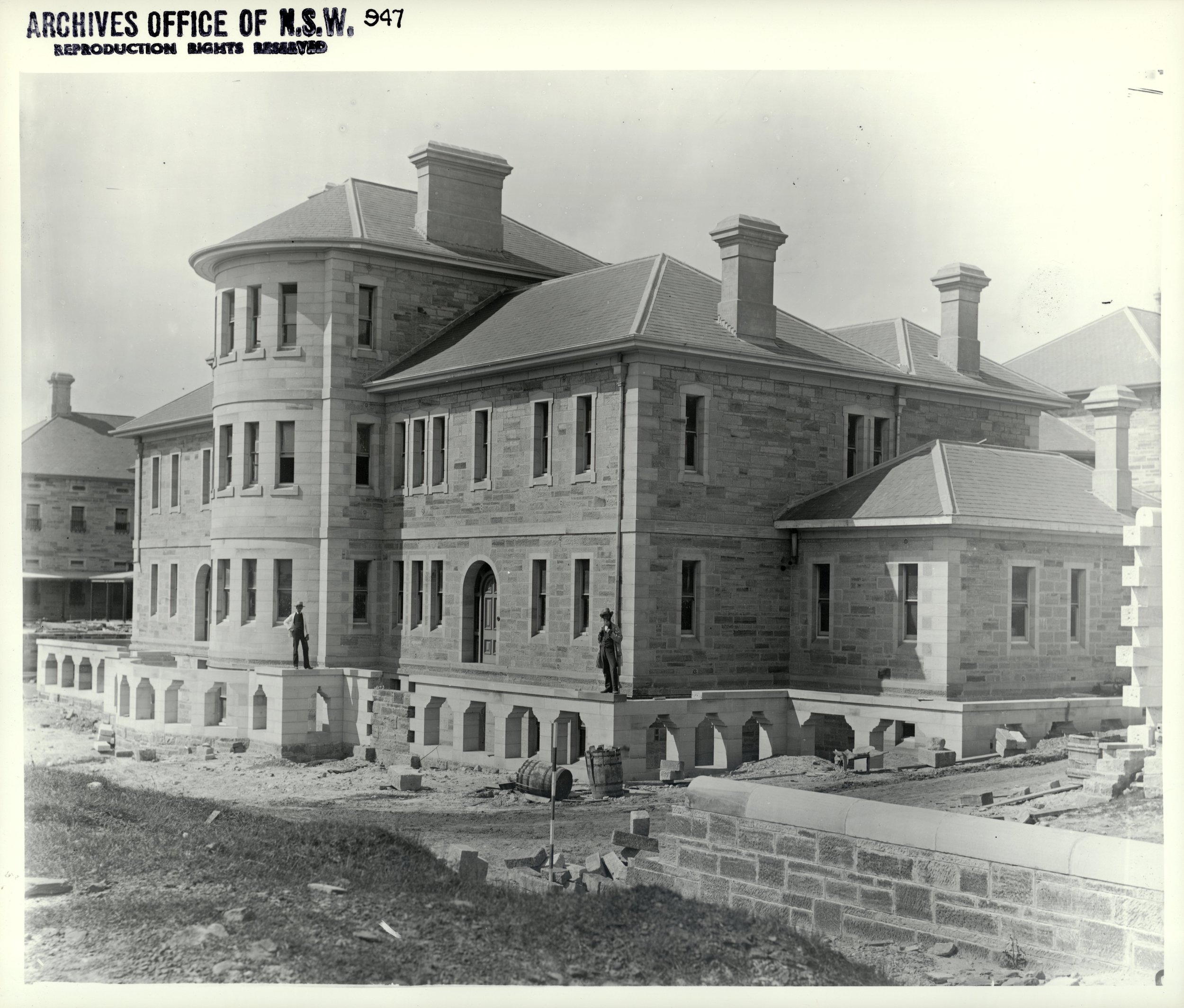

The NSW government architect James Barnet had gone to Callan Park to look at the subdivision and buy a two acre allotment for himself. He saw the potential of the site and the entire subdivision was acquired by the government for a new asylum.

During the building of the Kirkbride Block, Garry Owen House was adapted and used an asylum in 1875-76.

Biggest and priciest colonial construction project

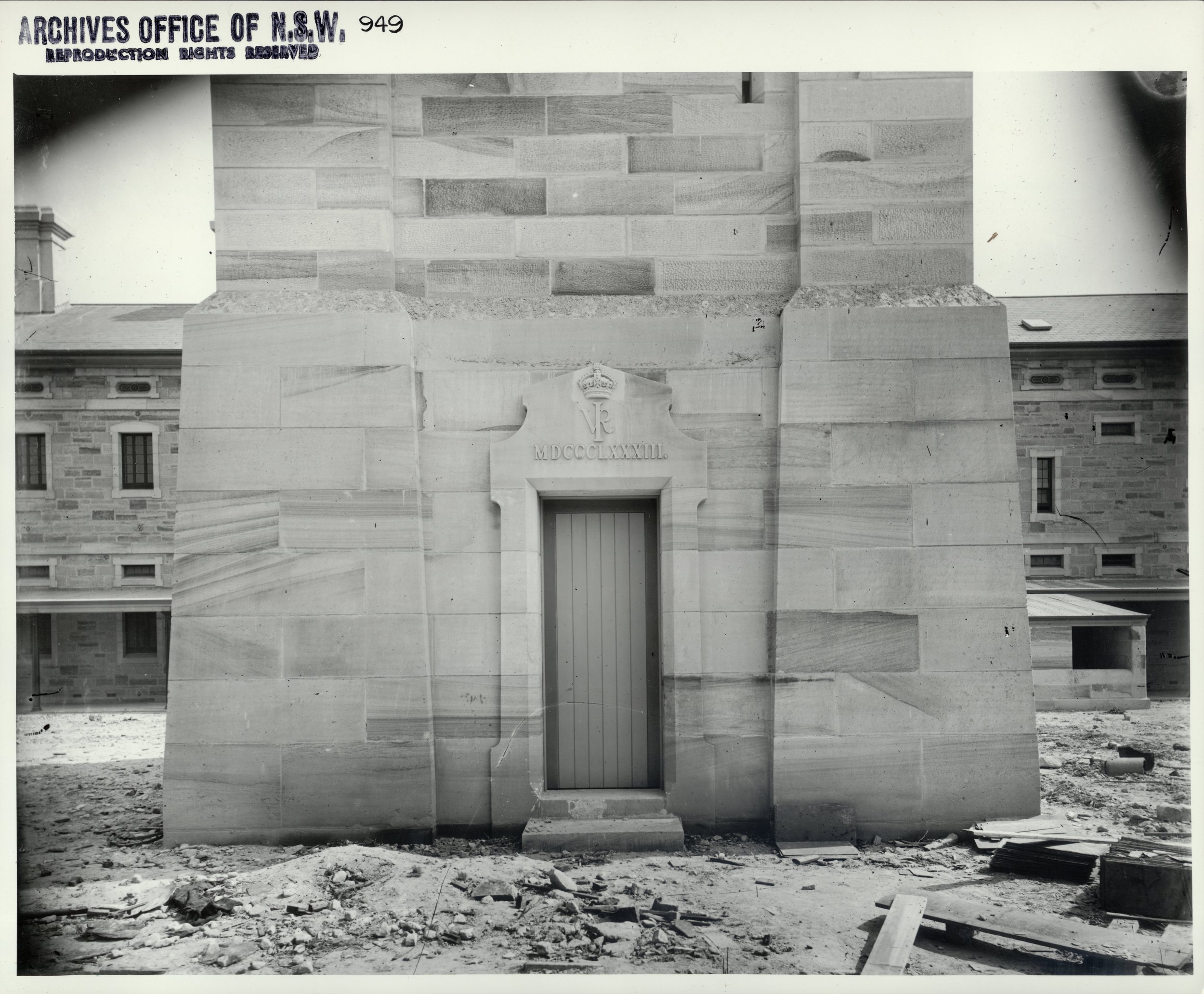

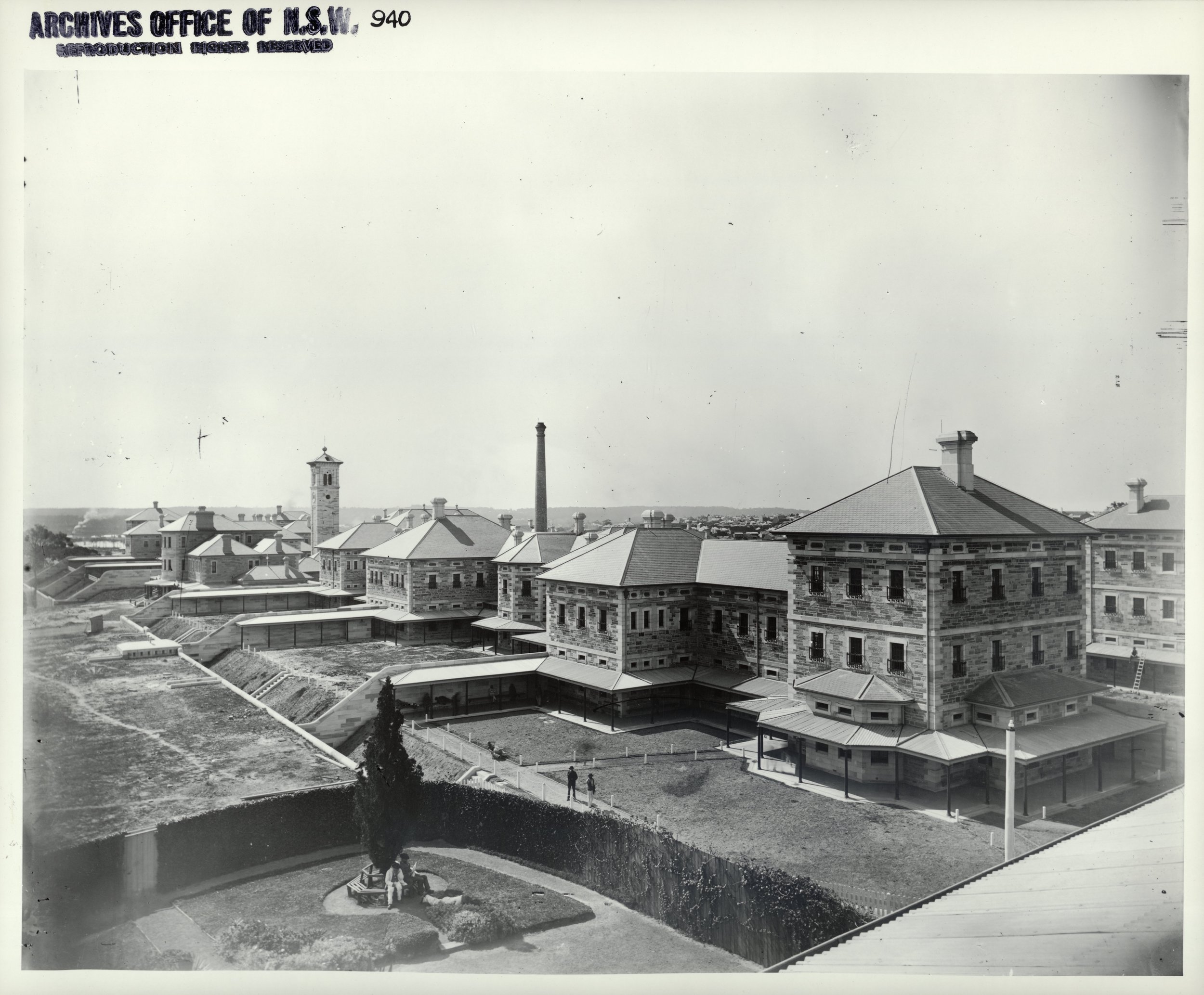

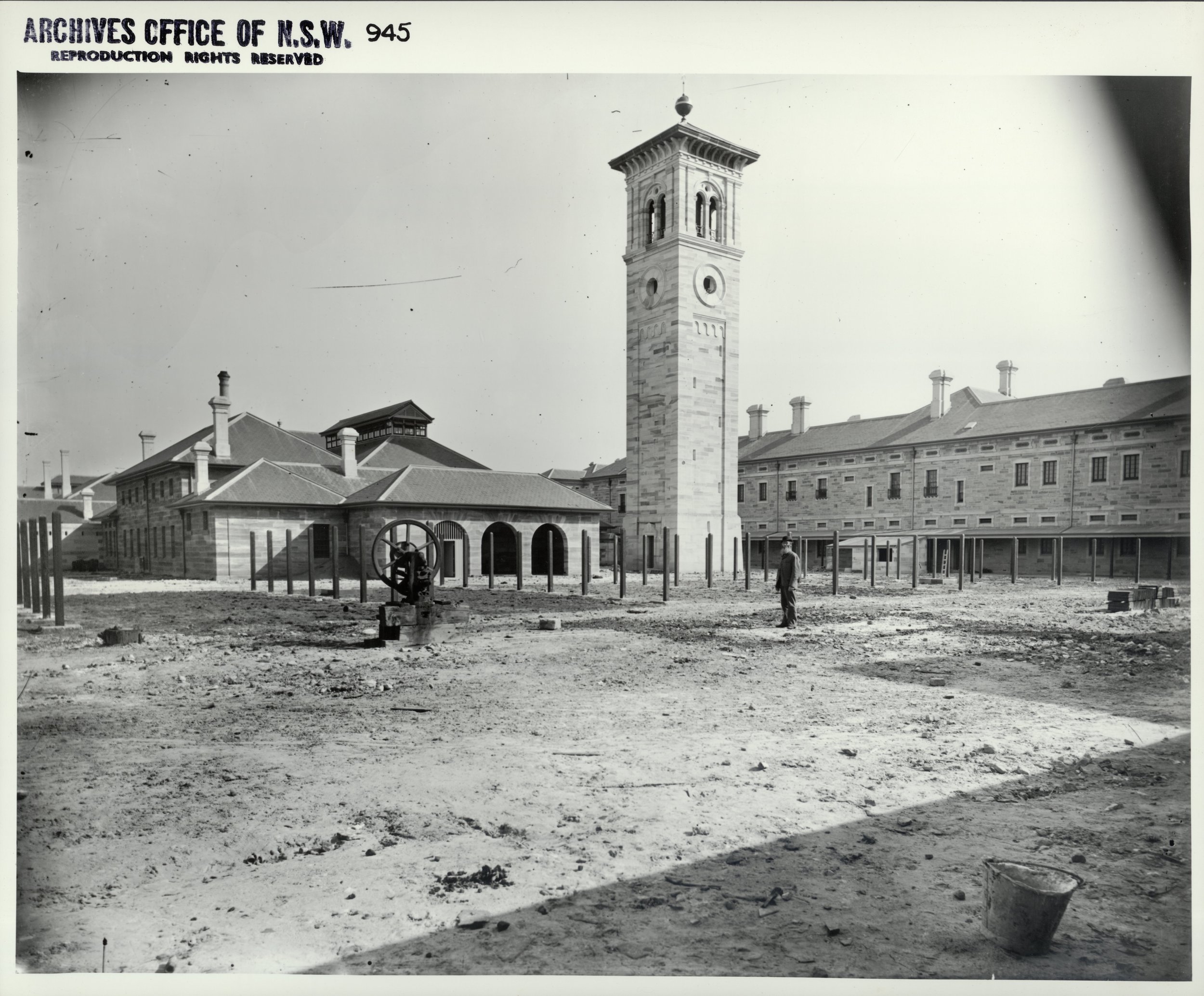

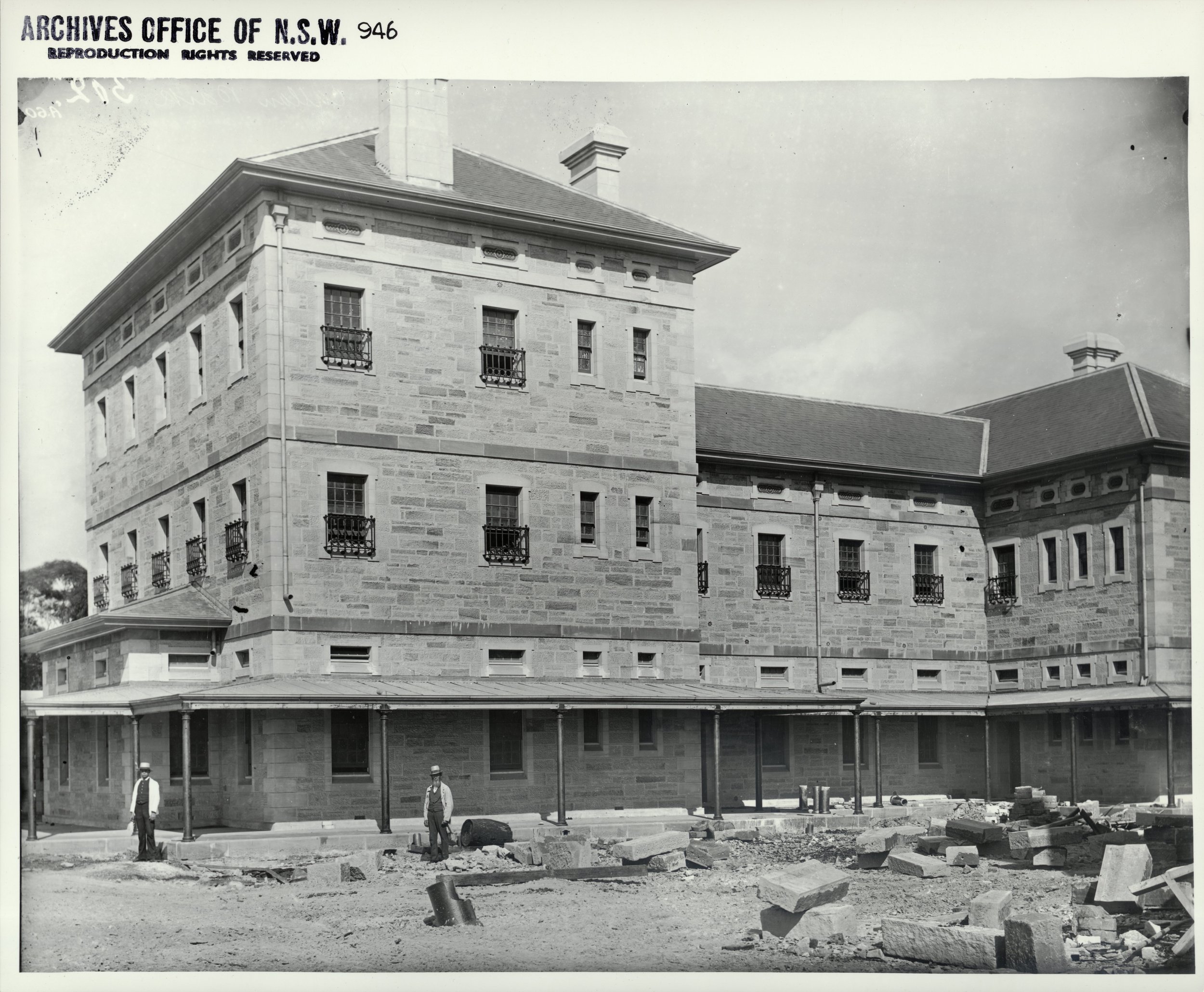

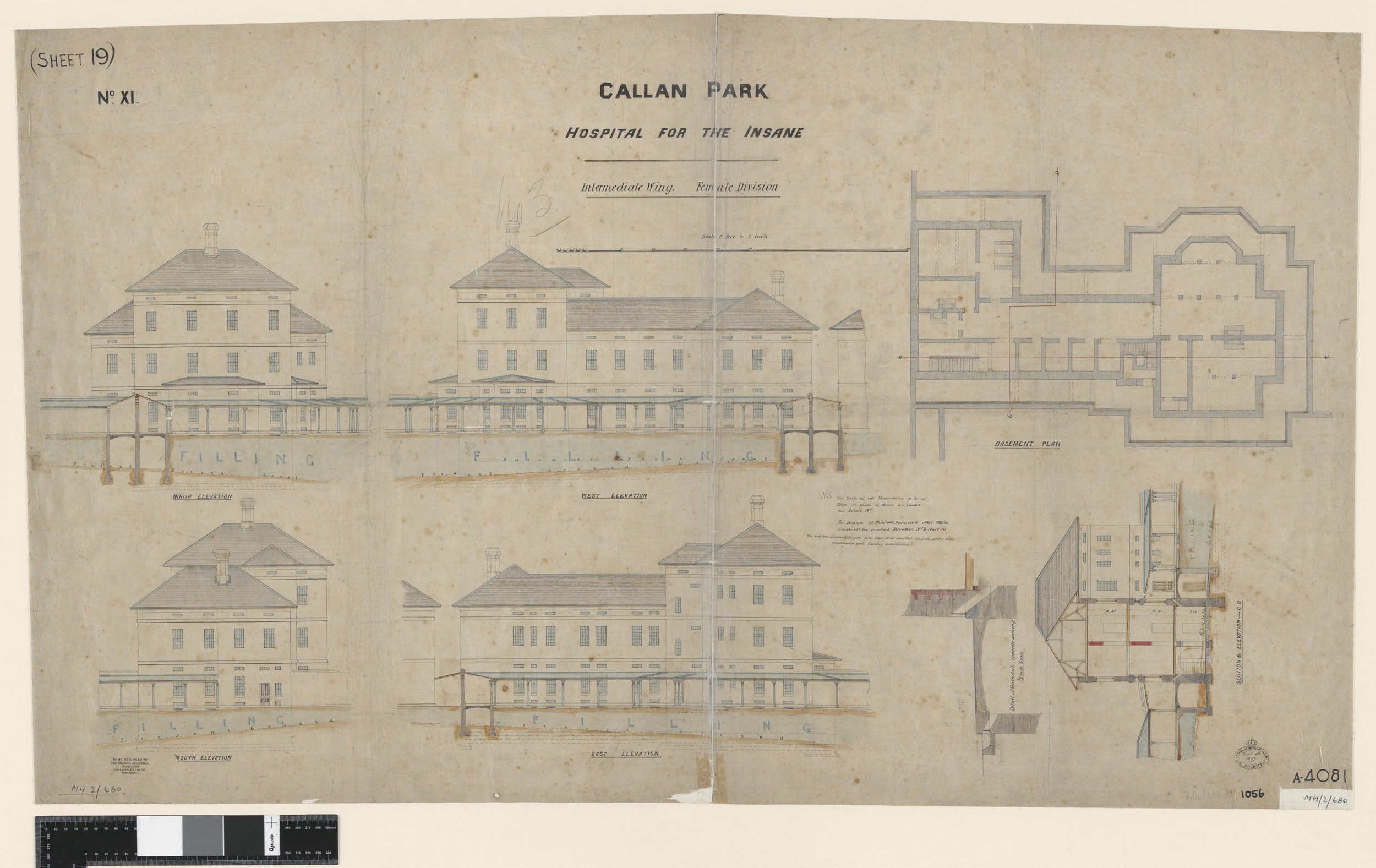

The design followed architectural principles set out by Thomas Kirkbride and was built bricks and with sandstone quarried on site. Known as the Kirkbride Block, the new asylum was finished by 1885. It was the largest construction and most expensive in the colony at the time.

According to the NSW State Heritage Inventory, Kirkbride Block is significant as:

“The collaborative work of three prominent figures in the late 19th century, James Barnet Colonial Architect (1865-90); Charles Moore and Frederic Norton Manning

the largest remaining mental institution in NSW, and

the first to be designed as a curative and therapeutic environment.

“The landscape cannot be separated from the buildings and performs an equal and active function in the creation of the therapeutic environment.”

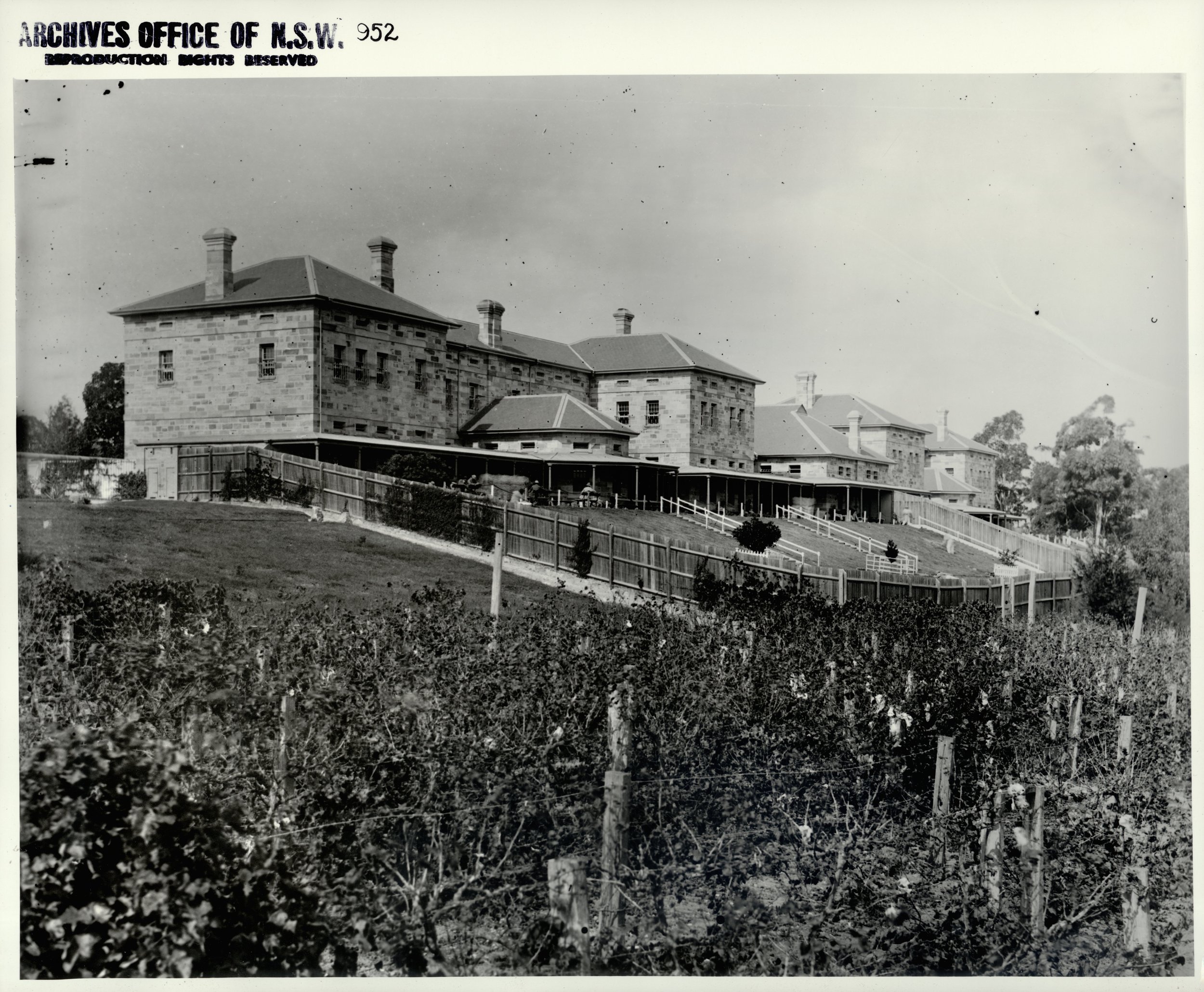

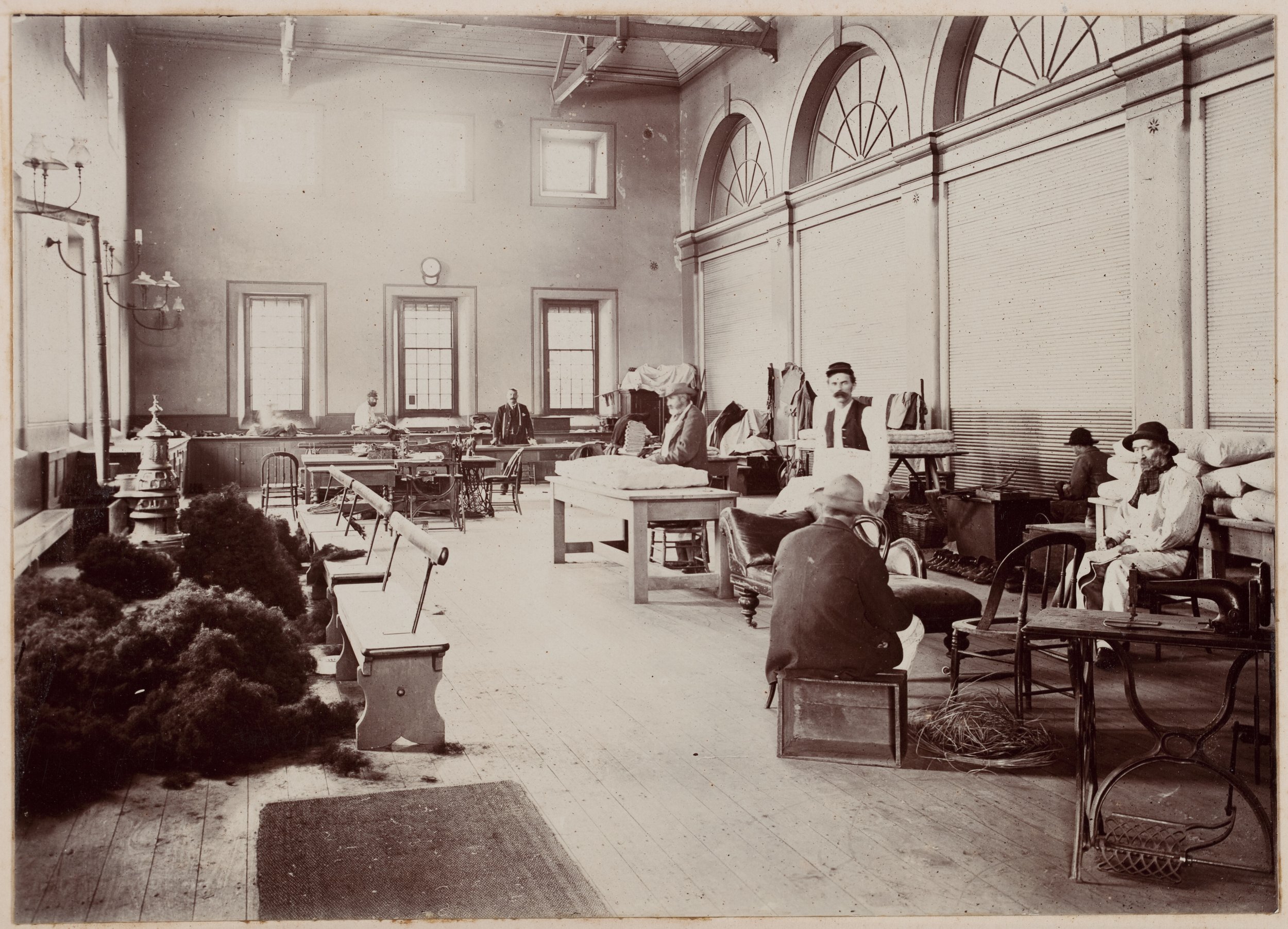

Largely self-sufficient, working farm

The back of the site that runs down to Iron Cove was a farm where patients worked, with vegetable gardens, dairy cows and a piggery.

Farms at mental asylums were not uncommon. It meant that Callan Park was largely self-sufficient in its early days.

Overcrowding and other issues emerge

In the late 19th century, and into the early 20th century, Callan Park Hospital for the Insane wasn't without issues. There was overcrowding, underfunding and understaffing. But its commitment to humane care, with patients working and being in nature, as part of their treatment, continued under Frederic Norton Manning.

Broughton Hall

Broughton Hall is on the western side of Callan Park. Formerly a private estate, the house and grounds were used as a convalescent home for returned soldiers from the First World War.

In 1921 Broughton Hall opened as a voluntary admission clinic for men and women psychiatric patients.

Mental Health Pioneer #2 Dr Sydney Evan Jones

Dr Sydney Evan Jones was one of Australia’s first psychiatrists and was an early adopter of psychotherapy.

As a young doctor, he’d joined Sir Douglas Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition in 1911. His interest in mental health stemmed from that trip, where people dealt with paranoia.

Sydney Evan Jones in Antarctica during the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914), from the collection of the State Library of NSW.

In 1925 Jones was made superintendent of Broughton Hall.

And he was on the same page as Mental health pioneer number #1 - Frederic Norton Manning, co-designer of Callan Park Hospital.

Jones believed that calming and beautiful surroundings were essential when treating mental health.

Flamingos and crocodiles in ‘Wonder Garden’

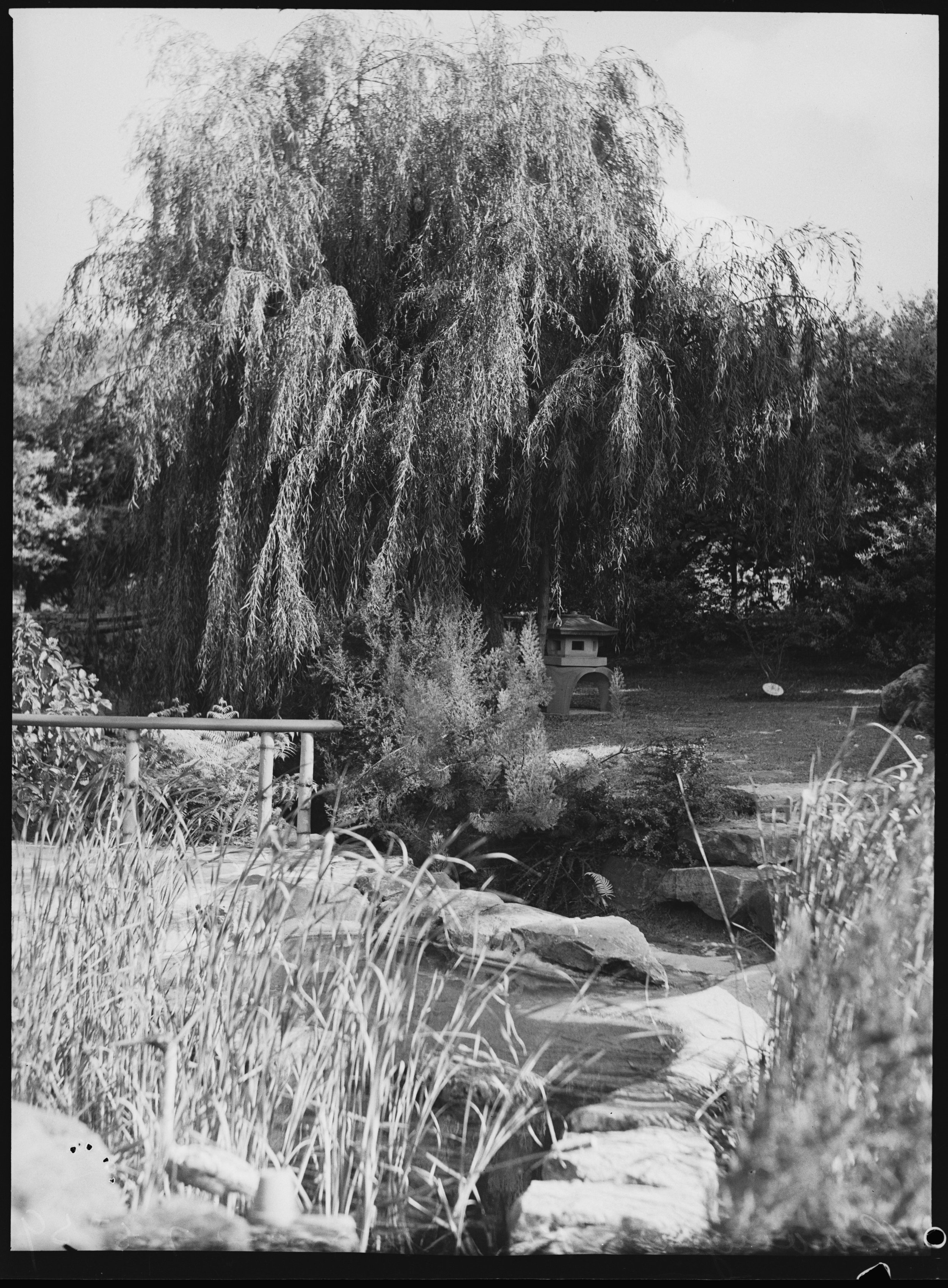

The use of gardens was an integral part of the patients' treatment. Winding paths, ponds and bridges were built throughout the grounds of Broughton Hall, under the direction of superintendent Sydney Evan Jones.

There’s a richly planted rainforest gully planted with New South Wales and Queensland rainforest trees and shrubs. The Medical Journal of Australia described the grounds as “building hills where none had been, valleys, sunken gardens, streams, bridges and stone walls.”

In August 1939, Smith’s Weekly newspaper in Sydney described on a ‘wonder garden’ created by Jones’ patients:

One of the most novel and decorative gardens in Australia has been constructed almost entirely by mental patients, at Broughton Hall Psychiatric Clinic, Leichhardt (NSW). It is part of the treatment to permit patients to do whatever interests them, and many of them have been keen on landscape gardening.

A council employee, while at the clinic, made a number of life-sized flamingoes, cranes and crocodiles, which now decorate lily-ponds and fish-ponds.

The general layout of the garden, which extends a couple of acres, is an arrangement of little paths leading into sunken gardens which have artificial waterfalls and gold fish ponds.

Trees and shrubs of all varieties are arranged to produce the best effect. The garden is also decorated with rustic bridges and Japanese arches, pagodas and dovecotes. One large pagoda is coloured red, yellow and green, and decorated with colored glass. Along the roof runs a dragon's body, with at each end a weird head bearing sparkling glass eyes.

It has been found that the atmosphere of this strange and enchanting garden does much towards soothing the nerves of patients and assisting in their recovery.

Standard of care drops at Callan Park Hospital for the Insane

In the 1920s, when Broughton Hall is all rainforests and flamingos, just up the hill at Callan Park Hospital, the standard of care has dropped.

Overcrowding and underfunding gets worse.

Royal Commission 1960-61

The biggest and most explosive exposure comes with a Royal Commission into Callan Park 1960-61.

They find evidence of cruelty, neglect and corruption and the Commission gets lots of media attention. Callan Park had become shorthand for all that was bad in mental health care.

“You weren’t allowed to go on the grass”

Peter Gray was a patient at Callan Park hospital in 1973 and 1975.

By the time Peter was a patient at Callan Park, the use of psychiatric drugs and electroshock therapy was entrenched. The idea of green therapy was lost.

Peter says that the buildings of the Kirkbride Block haven’t changed since he was a patient in Ward 2.

Despite the beautiful surroundings, Peter’s access to them during his stay was limited.

“There were times where I could actually see out the window, maybe just see between the building and see the view right across the bay.”

“It mightn't last long though, but I still was able to have that time, even confined to this ward.”

When he first came here, he says you weren't allowed to be on the grass. ”That was very strict and really bad.”

When he was a patient the second time in 1975, he said they’d relaxed the rules and you were allowed to lie on the grass.

When Peter was ‘let out’ of his ward, at lunchtimes or an weekend afternoon, he would walk around the grounds near KirkBride and down to the waterfront. “It certainly made you feel alive,” he says.

Peter Gray is now an active member of Friends of Callan Park.

“Waiting for the medication to work”

Jenna Bateman started training at Callan Park in 1980, as a mental health nurse. During that time, “people thought medication was going to cure people. Therapy that nature gives people did get lost.”

She used to take patients for walks, but she says the staff didn't connect it with with therapy, other than getting a bit of exercise.

“There wasn’t a connection that being in nature would be good for people mentally….And not just sitting, waiting for the medication to work.”

Jenna says she keeps coming back to Callan Park. She’s a member of their Bushcare group and the Community Garden, and is there at least three times a week.

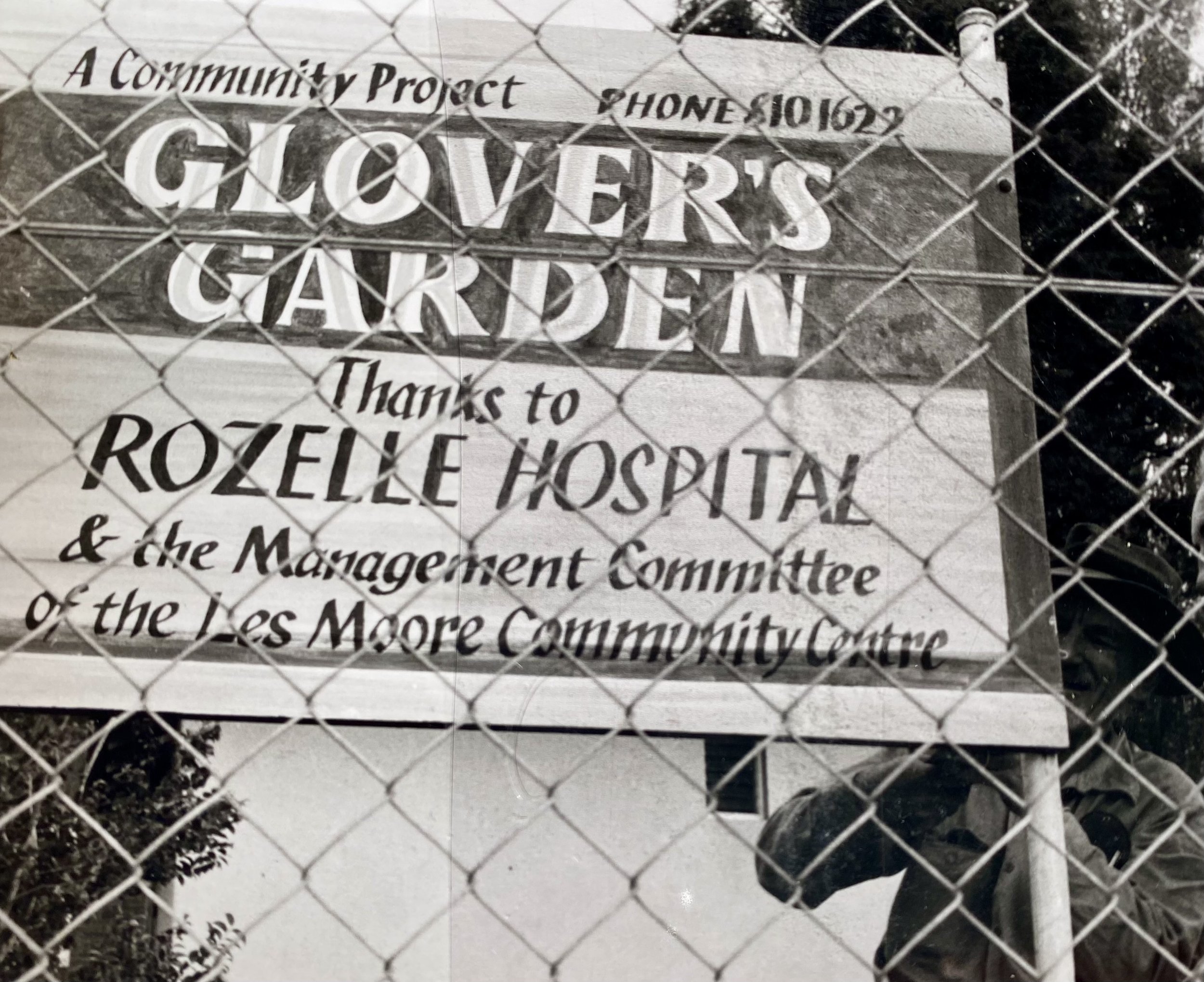

Glover Street Garden: Sydney’s oldest community garden

When the community garden was first set up in the 1980s by residents, patients from Callan Park were members too and gardened regularly. Like back in the old days!

The Glover Street Garden is on the eastern side facing the water.

The garden is thriving with regular gardeners like (L-R below) Emma, Jenna and Kimmy, and the Coordinator Stephen Gillespie (below right).

Callan Park Bushcare - the ‘green gym’

Bronwen Campbell has been volunteering with Callan Park bushcare for about twenty years, and these days she’s the coordinator.

Bushcare at Callan Park began with the work of Peter Jensen, she thinks.

He studied the remnant bushland around Callan Park when it was still a functioning hospital and later wrote a book, Natural heritage of Iron Cove, published by Greening Australia in 1998.

“He was fairly excited about what he found - a long list of native trees, grasses and ground covers.”

The trees that Peter Jensen found included black butt, ironbark, scribble gums and lots of wattle - around forty species in total. The area is Sydney sandstone (or Sydney Basin Hawkesbury sandstone) with a capping of iron bark turpentine at the top of the ridge, Bronwen says.

In 1995 a volunteer bush care group was set up, and has been running ever since.

These days the volunteer bush care group cares for about two hectares of bushland.

The bush care area begins near the substation on the eastern side. It wraps around king George Park to the water and then continues out to Callan Point and then down to the water and continues up the side of The Bay Run, enclosed by Central Avenue.

“You've got to come along for your weeding fix,” Bronwen says. “It's social, friendships are made and it's out in the open air so it’s very healthy. In fact, some people refer to it as the green gym.”

Bronwen finds bush care therapeutic too.

“There's something about being involved with both gardening and bush regeneration that connects you to the land. It makes you closer to nature. You notice the birds and the animals that are around the plants. And with a group of likeminded people, it's a very restorative activity.”

Another volunteer Adrianne agrees, but points out that for a bush care site, Callan Park is pretty noisy!

“It can be really noisy, from sports activity or dogs barking, or most of all airplanes overhead all the time.

“But it can be really therapeutic when you are with a nice group of people who all want to do the same thing - which is to preserve the bushland and expand it. We value nature, value the bird life, and the other biodiversity that goes with it.”

Friends of Callan Park

Friends of Callan Park is a community action group of volunteers who for over 22 years have been advocates for protecting Callan Park against sell-offs and development.

“The biggest pressures and the biggest dangers to Callan Park, over the last four decades, has been state governments, of both political complexions,” says Hall Greenland, President of Friends of Callan Park.

“Both of them have tried to sell off large parts of Callan Park for residential development. Fortunately, the community has been able to fight back.”

Roslyn Burge, longtime active member of Friends of Callan Park, says that they’ve been fighting for public open space and for psychiatric services first to be retained and then reinstated at Callan Park.

They’re asking the NSW state government to introduce ‘step up’ mental health services, for people building up to an acute episode, and ‘step down’ services for people when they're released from an acute site. “And there's certainly the accommodation to do that,” Roslyn says.

“Sometimes the debate was rather sharp because there’s some stigma about Callum Park as a place of torture and neglect and mistreatment of people,” Hall says. “And there was a great deal of that in the past. On the other hand, there was also success stories. “

Friends of Callan Park demand the establishment of a trust to secure its future, champion the long term restoration of heritage buildings, maintain the grounds and restore the site as a centre for wellness. Photo: Friends of Callan Park

‘We’re not just NIMBYs or champagne socialists’

Roslyn points out that local councils have surveyed local residents since 2001. And residents consistently say, we want mental health services to stay at Callan Park.

It is pretty amazing that this local community is community fighting to keep this beautiful park intact. Not just for themselves, but to share its therapeutic value with people who really need it.

“A big part of our [Friends of Callan Park] membership is people who are mental health advocates, recovered patients, people who've got children or relatives who are mentally ill or who have been mentally ill in the past,” Hall says. “And that’s a source of strength.”

Hall says that their committment to retaining and expanding mental health services at Callan Park “has given us a certain moral cache. We're not just greedy kind of champagne socialists or NIMBYs or whatever.

“We're people who recognise that this place has got social function and when we don't want it abandoned.”

“People are coming here to play sport. People are walking through here, and walking their dogs. It's good to have mental health services and people recovering from mental health conditions in the community.”

“This place is in the community.”

Some mental health services continue

Nearly 150 years ago, Callan Park was deliberately chosen to be a therapeutic landscape.

And although Callan Park Hospital closed in 2008, after more royal Commissions and de-instutionalisation, mental health services still exist there.

In 2008, the day after the hospital closed, the non-government organisation We Help Ourselves moved into buildings on the western side.

Executive director Garth Popple said the Rozelle Hospital grounds were the perfect location for WHOS due to its natural, peaceful setting and because it was not close to any busy residential areas.

"We provide services to people who are suffering from substance dependence, including people who have suffered addiction and mental health issues, which is sometimes called dual diagnosis," he said.

Foundation House at Callan Park offers rehabilitation for people in the construction industry with alcohol, other drug and gambling addictions.

First Nations understanding of mental health

Most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people see mental health in a holistic way.

Instead of the term ‘mental health’, there’s the term ‘social and emotional wellbeing’.

Things known to benefit social and emotional wellbeing are having a sense of belonging, and connection to community, culture, spirituality, ancestry, and land.

The AIATSIS literature review in 2011: The Benefits Associated with Caring for Country describes how:

the beneficial relationships held between Indigenous people and their country are encapsulated in sayings by Indigenous people such as ‘healthy country, healthy people’ and ‘if you look after the country, the country will look after you’.

The research on mental health, parks and green space

Xiaoqi Feng is a professor in Urban Health and Environment at the University of New South Wales School of Population.

Xiao has been trying to answer a question that governments and policy makers kept asking.

How much green space do we need?

Xiao‘s research shows that if you live in neighborhood with 30% or more tree canopy and green space, it's really good for your physical and mental health, reducing loneliness, anxiety and depression.

And this research is shaping Sydney - like the City of Sydney’s 2021 Greening Strategy, which aims for a 30% tree canopy and green space.

How parks differ in quality, for different people

Xiao emphasises that everyone has sees the quality of a green space differently. For example, if you're dog lover and if the park allows dogs off- leash, you may think this is high quality to you.

However, for the same reason some people might decide against going to this park and see it as low quality because they're scared about dogs running around.

“All parks are not the same. They're not equal and also not equal to everyone,” says Xiao.

“When we talk about quality, there are some features that everyone may see as ‘high quality’, but there are some things that should be customised for local residents, because that's the people you serve.”

Features of high quality green space

Xiao says that while everyone defines quality in our own way, in general, high quality parks are:

safe

clean

have biodiversity, and

have variety - you can do more than one thing there.

Once you crack those, the mental health of both kids and adults benefit.

Mental health benefits of high quality green space

Xiao’s research finds that women who after give birth, are living in high quality green space, reduce their risk of developing postpartum depression by 26%.

“We find children's mental health and pro-social behavior significantly better if they continue living near high quality green space.

In a longitudinal study (where you track the people over time), Xiao found that “children who always live with high quality green space have better mental health than their peers who are living with low quality green space.”

Over time, this difference increases, and “there's a big gap between the children who live with high quality and low quality green space, regarding their mental health wellbeing.”

Callan Park is a high quality green space

“Callan Park has a lot of variety and biodiversity,” Xiao says. “Callan Park is not only well positioned, but it’s well designed and people going there can do lots of things, not just one thing.”

As a high quality green space, Xiao's research then suggests that the natural landscape of Callan Park has a positive impact on mental health.

Links

Designed to Heal: the Sydney garden that may be the key to our mental health (Sydney Morning Herald January 2022)

The healing power of gardens by Oliver Sacks (New York Times April 2019)

Nourished by nature: Garden design for mental health and wellbeing (Sanctuary magazine October 2020)

Your daily dose of nature with Dr. Dimity Williams and Steven Wells the Gardener (Doctors for the Environment Australia podcast November 2020)

Got more links you think should be here? Let me know!